This article is part of a semi-monthly column on the history of roleplaying, one game company at a time. The intent is to step back and forth between larger roleplaying companies and smaller, related ones. Last column I covered Chaosium. This related article discusses Issaries Inc, one of the three companies which fractured off from Chaosium in the late 1990s.

This article was originally published as A Brief History of Game #4 on RPGnet. Its publication preceded the publication of the original Designers & Dragons (2011). A more up to date version of this history can be found in Designers & Dragons: The 00s.

Issaries Inc. is one of three new companies that emerged from Chaosium in the late 1990s (the others being Green Knights and Wizard’s Attic). However, the story of Issaries’ creation goes back further than that and has to do with gradual changes in Gloranthan rights.

The Rise, Fall, and Rise of Glorantha: 1966-1996

Glorantha is a vintage fantasy world that originated with Greg Stafford’s fictional writing in college starting in 1966. In 1975 Glorantha got Stafford into game publishing with Chaosium’s first board game, White Bear & Red Moon. Then in 1978 Glorantha settled into the genre in which most people would discover it: roleplaying, via Chaosium’s 1978 RPG, RuneQuest. Over the next several years Chaosium produced supplements that are still hailed as some of the best ever published.

In 1984 Chaosium decided to license RuneQuest to Avalon Hill, and along with it gave them some limited rights to publish Gloranthan RQ supplements. Unfortunately the partnership was rocky from the get-go, when Avalon Hill refused to place creators’ names on the RuneQuest box in violation of their contract. Nonetheless Chaosium kept working with Avalon Hill to produce RuneQuest publications, many of them Gloranthan, for a few years, with the result being classics like Gods of Glorantha (1985), Glorantha (1988), and Elder Secrets of Glorantha (1989). And then in 1989 the relationship frayed entirely. Chaosium ceased working with Avalon Hill and and Gloranthan publications stopped entirely.

Perversely, this caused an upsurge in Gloranthan fan activity. Reaching Moon Megacorp started publishing Tales of the Reaching Moon that same year and started holding RuneQuest conventions in 1990. The United States would follow suit in 1994. And, though he was no longer working with Avalon Hill, Greg Stafford continued creating Gloranthan products on his own, absent the RuneQuest rules.

The first of these was King of Sartar (1992), an in-world collection of primary source material published by Chaosium. A series of “unfinished works”–each of them a photocopied book of Stafford’s original histories and backgrounds–would follow. These were semi-professional publications, not put into gaming distribution channels. The first was The Glorious ReAscent of Yelm (1994), published for the American RQ-Con.

At the same time Avalon Hill started publishing new Gloranthan work under the auspices of Ken Rolston, but Chaosium had very little to do with the publications, and this soon became obvious, such as when Michael O’Brien’s Sun County (1992) was contradicted by Stafford’s Glorious ReAscent of Yelm (1994), an event which led to the creation of the term “gregging”, to describe Stafford making a new discovery in the world of Glorantha that might contradict fan publications.

Back on Target: 1996-1998

Things really began to turn around for Glorantha in 1996. A deal began to gel between Chaosium (then still the prime holder of the Gloranthan IP) and an Italian game company Stratelibri to produce a 25mm Gloranthan miniatures game. Simultaneously Dave Dunham was working on a Gloranthan computer game called King of Dragon Pass. With these two Gloranthan projects requiring support, the success of the Mythos CCG bringing money into Chaosium, and fans continuing to express interest in Greg’s unfinished works, Chaosium went ahead and hired a Gloranthan editor, Rob Heinsoo.

In the first issue of Starry Wisdom, a Chaosium quarterly funded by Mythos sales, Heisoo reported an ambitious roll-out for a post RuneQuest Glorantha in an article called “Putting Glorantha Back on Target”. It included plans for six new Gloranthan lines: the 25mm Stratelibri skirmish miniatures game; a 15mm mass combat miniatures game; Dave Dunham’s computer game; a new line of systemless Gloranthan sourcebooks; a new line of Gloranthan fiction; and eventually a brand-new Gloranthan RPG.

Unfortunately in 1996 the CCG market began to crash. Chaosium’s Mythos game simultaneously faltered with the overproduction of the Mythos Standard Game Set. Then in 1997 the general downturn in CCG fortunes led to a Magic crash in Italy. Not only was Chaosium hurting for cash, but their Italian partner Stratelibri could no longer fund a Gloranthan expansion either. Rob Heinsoo was laid off, and the dream of a new Gloranthan game from Chaosium died.

With Chaosium’s financial situation growing increasingly bleak, Stafford eventually decided that his own interests and Chaosium’s were no longer in sync, so he left the company that he’d founded over twenty years previously. Issaries Inc. was created as a new company to hold the Gloranthan trademarks and copyrights, separate from the more volatile highs and lows of its parent company.

One of the more interesting stories related to Issaries has to do with its foundation. It got off the ground by going out to its fans. In August 1997 Chaosium issued a press release offering fans the right to buy shares of Issaries for $100 each, with the plan being that the company would get going when $50,000 had been raised. When the company was founded, it was promised that a new Gloranthan game would be just 18 months off.

Issaries was officially incorporated on November 20, 1997, but the plan for Issaries to raise money turned out to be not quite as easy as hoped due to 50 different legal regulations in 50 different states. The target number of 500 contributors also happened to be the exact number which would have forced Issaries to start reporting its finances officially and publicly (as Wizards of the Coast had also discovered in the same time period). It would be 1999 before the legalities were figured out, but in the meantime work was progressing on the new RPG.

The Creation of Hero Wars: 1998-2000

Stafford had been trying to produce a non-RuneQuest Gloranthan game for years, but the difficulty of creating a fully scalable system which could accommodate both Balazaran barbarians and high-powered heroes had always been a major roadblock. But then Stafford learned that Robin Laws, already an upcoming designer with both Over the Edge and Nexus: The Infinite City under his belt, was a Gloranthan fan. Stafford approached him to create a new game.

By 1998 the game then called Glorantha: The Game was well underway. It was being playtested at Chaosium with Stafford gamemastering a regular game. The design of the game was a considerable step away from RuneQuest. Designed twenty years previously, RuneQuest was (and is) a fine example of a simulationistic character-based system. Conversely, Glorantha: The Game was straight from the storytelling branch of games, designed by one of the main proponents of those games.

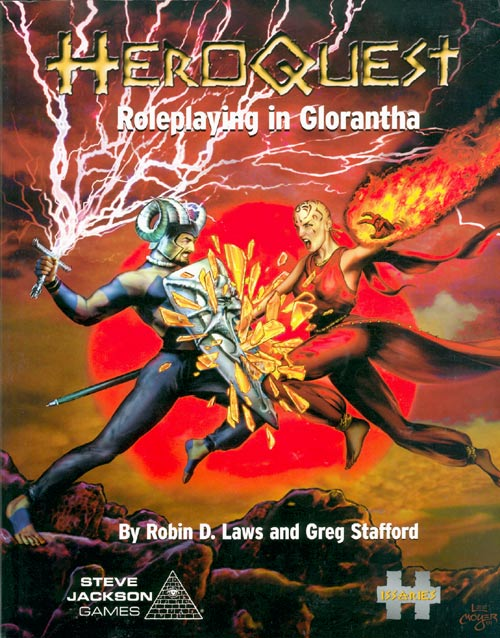

By mid-year the game had a real name. Hero Wars. Stafford had wanted it to be HeroQuest, a game that he’d been promising for twenty years, but Milton Bradley had grabbed the trademark when Stafford had let it lapse some years previous. So, Hero Wars it was.

Hero Wars was first demoed to the public in May, 1998 at the American Glorantha-Con VII. At the last minute the decision was made to create some t-shirts for the event. They’d highlight the convention and the fact that it was the public unveiling of the new Glorantha game. I was working at Chaosium at the time, and I was the one who ended up making those shirts, which read “Hero Wars: The Initiation”. A Hero Wars logo of some sort was needed, so I laid out the words in a simple font without paying much attention to them. (For a later iteration of the logo, I’d knock bits out of the letters to make them looked aged.) When I laid the logo out for the t-shirt, I printed it in bright orange, figuring it’d be very visible against the black shirt.

I never imagined that I was designing the logo that would be used, down to the bright orange color, on the Hero Wars books for years to come. Recently Warner Brothers and CBS learned this lesson too, when they unveiled their new network and gave it the “temporary” name “CW”. Temporary names and logos often aren’t, so do them right the first time, no matter how limited the audience is supposed to be.

In Feburary, 1999 the Glorantha Trading Association was finally founded. Members were now officially “patrons” and “supporters” rather than “share holders”, which helped avoid the need to meet the requirements of 50 different states’ security laws. The target money was shortly raised, and an 18-month deadline was set for the release of the new Glorantha game.

Hero Wars & HeroQuest: 2000-2004

In 2000 Hero Wars was finally released. It was, and remains, an innovative game system in the storytelling branch of RPGs. Some of the most interesting aspects include:

- A narrative character creation system, which allows players to describe a character, then turn that description into his initial stats.

- A totally freeform skill system, where any descriptive element can be a skill, allowing players to have exactly the appropriate skills for their characters.

- A unified task system that allowed the exact same resolution systems to be used for combat, debate, or any other action or interaction.

- A fully scalable skill system which made it easy to deal with characters at dramatically different power levels

However, there were also issues with the new game.

For one the game had been published in a very odd format: as book-sized trade paperbacks. At the time that decision was made, Chaosium had been doing well publishing their Call of Cthulhu line of fiction. And, in addition, an increasing number of game stores had gone out of business due to the CCG crash of the late 1990s. Wizard’s Attic, then a Chaosium subsidiary, was pushing hard on selling everything to book stores, and it was believed that if Hero Wars was published as books, it would sell in book stores too, providing an alternative market to the ailing game trade.

It never did, and the decision to publish as trades might have even hurt the game because the smaller format constrained layout and kept the books looking very basic; as well, they probably didn’t fit in well with most game store displays. The odd format would be scrapped after the initial release of Hero Wars products.

Beyond that, many felt like the game was rushed out. Even Stafford agreed with this assessment, but initial funds had run out and the 18-month deadline was up, so the choices were to release the game in its unpolished state, or not at all. The game went out

From 2000 to 2002 a good number of Hero Wars supplements were produced, including many that offered extensive coverage of the Sartarites, a long neglected Gloranthan culture. Though the original game had been unpolished, these first supplements provided a much more solid foundation for the game line. They were books that Glorantha fans had been waiting for for almost twenty-five years.

In 2003 Issaries sold out on its original Hero Wars run and decided to revise the Hero Wars rules in a second edition. The rulebook was finally polished and published in a standard RPG form. Even better, the Milton Bradley trademark had lapsed, and so Stafford was able to publish the second edition of his Gloranthan game under the name he had always wanted: HeroQuest. If this considerably better rulebook had been the first one published, the new game might have been more successful from the start. In 2003 and 2004 it would be supported by another half-dozen supplements.

Unfortunately the RPG business has contracted quite a bit in the last few years, and as a result a company producing a game like HeroQuest is now, out of necessity, tiny. Issaries never supported more than a single full-time employee, and has typically been run out of the California Bay Area, one of the most expensive places to live in the country.

Partially due to these financial issues Greg Stafford moved to Mexico for a year in 2004, and at that time Issaries’ production dried up. The last HeroQuest books produced were Gathering Thunder (2004), another Sartarite book, and Men of the Sea (2004).

A Changing Future: 2005-2006

Stafford returned to the United States in 2005, and since then Issaries has taken a different tack, and one that will probably prove more successful for Glorantha. Rather than trying to publish Glorantha books itself, Issaries is instead licensing out the rights to other companies who can better provide the time and resources. Thus, Issaries has become a rights holding house, much like Marc Miller’s Far Future Enterprises, or FASA after it closed up shop in 2001.

Issaries currently has at least three licensees. Mark Galeotti’s Firebird Productions has licensed the HeroQuest system to create a Mythic Russia RPG. Rick Meints’ Moon Design Publishing company, which had previously produced licensed RQ2 reprints, has taken on HeroQuest itself. They’ve already published one supplement, and will generally be continuing on where Issaries left off. Mongoose Publishing, meanwhile, has licensed the RuneQuest system (after Hasbro, the purchaser of Avalon Hill, decided to let the trademark expire), and they have released a new RuneQuest core book, with a series of supplements and miniature figures in the pipeline.

And now that he no longer has to publish the games himself, Stafford is back to doing what he started with in 1966: writing fiction.

The world of Glorantha has seen many Renaissances, including: the 1975 release of White Bear & Red Moon; the 1978 release of RuneQuest; the 1992 resurgence of Avalon Hill materials under Ken Rolston; the 2000 release of Hero Wars; and the 2003 revision of HeroQuest. 2006 may well mark another turning point, and though Issaries is now receding from public view, it still remains at the heart of these new licenses.

For a polished and somewhat expanded version of this history, see Designers & Dragons: The ’00s.

Thanks to Greg Stafford for his comments on this article. Other information is drawn from Starry Wisdom magazine and my own experiences working at Chaosium.