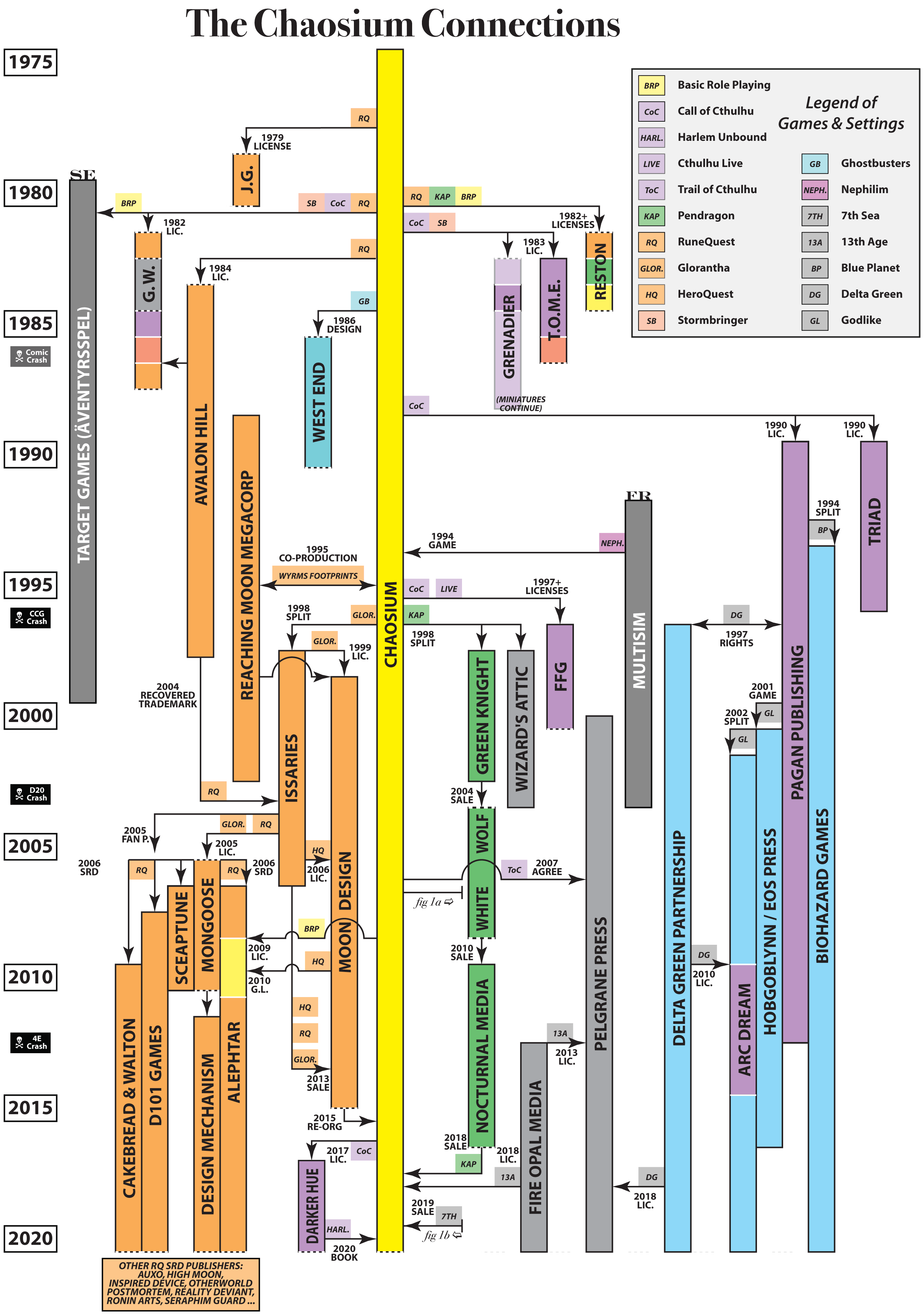

Some years ago, one of the earliest articles written for Designers & Dragons was a look at Chaosium’s connections in the roleplaying industry. What follows is an update of that classic article that adds fourteen years of new connections and cleans up a few old ones.

Not every company in the industry works regularly with others. ICE is an example of a company that largely went their own way, focused on their Middle-earth license and their Rolemaster system, while Hero Games regularly teamed up with other companies in the ’80s (and even joined ICE!). But it’s possible that Chaosium may be the company in the industry with the most personal connections, thanks to its generous licensing in the early days, and due to a variety of factors since.

More than just a focus on Chaosium, this article also shows several major trends in the roleplaying industry over the decades.

Note that this is primarily a list of companies whose English-language book publications are linked to Chaosium in some way. It doesn’t include foreign-language licenses (with two exceptions), nor licenses for other physical articles like t-shirts, buttons, fiction, props, or miniatures (unless they also published books), nor does it include licenses for audios of games or podcasts, nor does it include fan organizations (again, with one crucial exception). Expanding into those areas would have made this complex chart into an insane one.

The Multiple Licensors

Some of the earliest entrants to the industry were companies that picked up multiple licenses, either to produce supplements (Judges Guild), to bring products into a foreign market (Games Workshop), or to bring them to the mass market (Reston).

Games Workshop (1982): In the mid ’80s, creativity was flowing both ways across the Atlantic. US publishers were actively reprinting the British Fighting Fantasy books while UK publishers were reprinting lines like Tunnels & Trolls. Games Workshop wanted to get in on this, and so around 1982 they reprinted some of the RuneQuest 2 books, and then from 1985-1987 they published their own high-quality versions of Call of Cthulhu, Stormbringer, and RuneQuest for the British market. They also did a few original supplements for Call of Cthulhu that were sold on both sides of the pond. Then Warhammer miniatures ate their soul.

Judges Guild (1979): Chaosium’s first licensee, and at a time one of the most frequent publishers in the industry. They’re best known for their (official) AD&D supplements, but they also did a half-dozen RuneQuest supplements, the most notable of which is Broken Tree Inn (1979), which contained material originally intended for Chaosium’s Snake Pipe Hollow (1979). Hellpits of Nightfang (1979) and Legendary Duck Tower (1980) are also quite well remembered.

Reston Publishing (1982): A publisher of hardcovers for some of Chaosium’s books, plus The Adventurer’s Handbook (1984). A Prentice-Hall Company, and thus an early attempt to move RPGs into the mass-market.

Design House Dreams

As is so often the case with roleplaying companies (and was particularly true in the ’70s and ’80s), the early principals of Chaosium were interested in designing games, not running a company. Thus they flirted with the idea of being a design house in the mid ’80s, where other companies would take care of the production and distribution of their games. This didn’t work out particularly well for them.

Avalon Hill (1984): That started with RuneQuest, which Chaosium licensed to Avalon Hill, along with some rights for Glorantha. Avalon Hill never published at the higher levels that would have been required for this work financially for Chaosium, and as a result Chaosium almost went out of business, then had to abandon their top RPG. Avalon Hill themselves stopped publishing RuneQuest in 1994 and were purchased by Hasbro in 1999. They’ve since become a brand name for Wizard of the Coast’s board game line, while Issaries has recovered the RuneQuest trademark.

West End Games (1986): Chaosium designed the Ghostbusters RPG (1986) for them, which debuted the d6 game system which later became the core of West End’s game line. Although this wasn’t a disaster for Chaosium like the Avalon Hill situation, they likely didn’t see much upside, while West End built their entire company around the result.

The Early Cthulhu Licenses

Chaosium’s most popular game for licensing in the ’80s and ’90s was Call of Cthulhu. That’s in part because RuneQuest was gone, so Cthulhu became their core game. The licenses of this era were typical of the time: an occasional semi-professional to professional company was created because the principals wanted to support a particular line. But they weren’t too numerous because even following the ramp-up of desktop publishing in the late ’80s, there were still considerable barriers to entry for RPG publishing.

Fantasy Flight Games (1997): Probably Chaosium’s most financially successful licensee. They got off the ground publishing Call of Cthulhu adventures, but pretty soon they’d put out Twilight Imperium (1997) too, and they were off and running toward becoming a big-name board-game manufacturer. Their Call of Cthulhu (and Cthulhu Live) lines just lasted from 1997-2001, though later they had long-lived lines based on Arkham Horror (2005-2011, 2018-Present), which they later bought outright, and a Call of Cthulhu CCG (2005-2015). They’ve since become part of the Asmodee megagoliath.

Grenadier (1983): Grenadier was just one of several miniatures licensees (also including Lance & Laser, RAFM, Ral Partha, and Trollkin Forge) and that category of licensing isn’t generally listed here. However, Grenadier also put out a single Call of Cthulhu module in 1984, probably in an attempt to tell more people about their miniatures.

Pagan Publishing (1990): A very prolific Call of Cthulhu licensee who got started with The Unspeakable Oath magazine (1991-2001+), and then went on to produce some of the best-loved supplements for the game in the ’90s, including of course Delta Green (1996) — all during a time that Chaosium’s own Cthulhu line was struggling creatively following the departure of Keith Herber and the end of his popular Lovecraft Country products. Pagan’s principals have gone on to form other companies and publish other games, totally separate from Call of Cthulhu, in one of the cases where Chaosium’s initial influence has been multiplied.

Theater of the Mind Enterprises (1983): An early Call of Cthulhu licensee who put out some well-respected adventures and later published a single Stormbringer adventure too. They’d go on to publish Tékumel for a time.

Triad (1990): A short-lived Call of Cthulhu licensee who put out half-a-dozen books, but was entirely overshadowed by Pagan Publishing at the time.

The Pagan Pubishing Spinoffs

The success of Pagan Publishing can be marked not just by their acclaim, but also how they in turn spun-off several companies of their own over the years, first when they moved, and later when they started to decrease their publications.

Arc Dream (2002). In the modern day, Arc Dream is a full-on successor to Pagan. The company was formed to support Godlike (2001), a game that Dennis Detwiller had originally published through Hobgoblynn Press, but in the late ’00s they started working on Delta Green products with Pagan before taking over the line themselves.

Biohazard Games (1994). A company that split off from Pagan when John Tynes moved the company to Washington state so that he could join Wizards of the Coast. They’re best known for Blue Planet (1997), inspired in part by Pagan’s plans for an “End Times” supplement.

Delta Green Partnership (1997). The actual owners of the Delta Green property, created after the release of the original book (1996). They are Adam Scott Glancy, Dennis Detwiller, and John Scott Tynes, the creators of that supplement.

Hobgoblynn/EOS Press (2001). A company formed to publish Dennis Detwiller’s Godlike (2001), which had been prepared for publication by Pagan before they started to wind down around 2001. The company became EOS Press in 2003 and EOS SAMA in 2010 and moved on to a variety of more indie games before fading away in recent years.

The Near Connections

A few connections were so loose that they didn’t really happen (and also tended to be one-offs, like a few later companies in this listing).

Fantasy Games Unlimited (1983): In the same year, Fantasy Games Unlimited (FGU) published two different games clearly derived from BRP: Other Suns (1983) and Privateers and Gentlemen (1983).

TSR (1980). In Deities & Demigods (1980), TSR include Cthulhu and Melnibonéan mythos that Chaosium held licenses to. Chaosium agreed to allow TSR to continue using the setting material with a thank you in exchange for the right to use D&D in a future product. Chaosium thus produced Thieves’ World (1981), a multi-game supplement including D&D rules, while TSR published only one printing of Deities & Demigods with the acknowledgement to Chaosium, before cutting it entirely so as not to mention another RPG producer.

The Foreign Publishers

Chaosium has had many foreign licenses, and this article doesn’t try to list them all, but there were two of particular note.:

Multisim (1994): Multisim’s core game, Nephilim (1992), was BRP-based, and this led Chaosium to translate the game and publish an edition of their own (1994). Unfortunately, Chaosium quickly learned that in the ’90s it was just as expensive to translate a game as it was to produce something new. Meanwhile, the game never found its footing in the US, in part due to a rush to market (for Gen Con publication) and in part because Chaosium had one of its periodic crashes several years on, in the late ’90s.

Target Games / Äventyrsspel (1982): Another notable foreign licensee for their translation of Worlds of Wonder (1982) as Drakar Och Demoner (1982), which was the best-selling Swedish RPG for a decade, though it slowly left behind its BRP roots. They also used BRP as the basis for Sweden’s #2 game, Mutant (1984). Theirs is the story of how Chaosium created an entire industry in a foreign country.

A partial list of other licensees includes: ACE Pelit Oy, Ars Ludi, Beneficium, Dayspring Games, Descartes Editeur, Edge Entertainment, Éditions Sans-Détour, Enterbrain, Galmadrin, Grifo Edizioni, La Factoría de Ideas, Fanpro, Hobby Japan, Hobby Products GmbH, Joc Internacional, Laurin Verlag, Nosolorol Ediciones, Oriflam, Pegasus Spiele, PRO-Games, Stratelibri, Welt der Spiele, and Wydawnictwo MAG.

The Great Split

The CCG crash of the late ’90s caused Chaosium to split apart, with three different companies ending up with rights, leaving Chaosium itself with just Call of Cthulhu and Elric!/Stormbringer.

Green Knight (1998). Peter Corless’ company, which took the Pendragon rights due to a loan that Chaosium defaulted on — but Corless only took the game because Chaosium indicated that they’d no longer be printing it.

Issaries (1998). Greg Stafford’s company, which took the Gloranthan rights with it.

Wizard’s Attic (1998). Eric Rowe’s fulfillfment company, which started out as Chaosium’s online store of Cthulhu merchandise. They had many further connections with customers, most of them young d20 companies.

The Issaries Licenses

Greg Stafford’s Issaries had a go at publishing on their own for a few years, but then Stafford decided that he’d prefer to have others do that work.

Mongoose Publishing (2005): By 2005, Issaries (and thus Greg Stafford) owned the Gloranthan setting and the RuneQuest trademark, so they licensed Mongoose to create a new RuneQuest (2006, 2010) game (with background material set in the Second Age of Glorantha). This agreement lasted for several years, until Mongoose decided to take their game system their own way as Legend (2011).

Moon Design (1999): Originally licensed to reprint old RQ2 material, but they later got a license to Issaries’ HeroQuest line, and eventually bought all of the rights to Glorantha, HeroQuest, and RuneQuest.

A few Issaries connections to other companies on this chart aren’t shown, because of the chart’s focus on Chaosium connections. But Issaries also licensed Multisim in 2000 to translate Hero Wars products and they licensed The Design Mechanism in 2010 to continue the RuneQuest trademark following Mongoose’s departure from the fold.

The Mongoose Successors

Mongoose released their version of RuneQuest under an OGL, allowing anyone to produce content for it. This coincided with an increase in the ease of creating and selling PDF content. Together these factors turned RuneQuest into one of the most popular OGL systems of the ’00s (alongside d20, Fate, and Mutants & Masterminds, each of which had their own licenses).

As the chart notes, many OGL publishers are not listed, including Auxo, High Moon, Inspired Device, Postmortem, Reality Deviant, Ronin Arts, and Seraphim Guard. Many actually published quite a few products, some print products, or were otherwise notable. What’s shown are mostly those companies who have continued publishing into the modern day and who have the largest catalogues (and as it happens, all of the more long-lived companies also have their own version of Mongoose’s RuneQuest rules, all but one produced under the OGL).

Alephtar (2007). Though they got their start with OGL RuneQuest supplements, the Alephtar principals are clearly big fans of Chaosium, because they also licensed BRP from Chaosium and HeroQuest from Issaries. In the early days, they used this to produce setting books for everything from soldiers of Rome to the nomads of the Steppes. More recently they produced their own Revolution d100 (2016) game.

Cakebread & Walton (2010). Originally produced the evocative 16th century Clcockwork & Chivalry (2010) setting for RuneQuest, but they quickly moved on to their own Renaissance (2011) version of the game system.

D101 Games (2008). D101 received a license to publish a Gloranthan fanzine under Issaries’ 2005 fan policy, resulting in Hearts in Glorantha (2008+). They then used the OGL to publish their own version of Mongoose’s RuneQuest called OpenQuest (2009). In more recent years, they’ve also published their own OSR game, Crypts & Things (2012).

Design Mechanism (2012). The creators of the second edition of Mongoose RuneQuest formed their own company after they left Mongoose, where they licensed Issaries’ RuneQuest trademark to publish RuneQuest 6 (2012), a new version of the game that they rewrote from scratch. So, they have the only successor game to Mongoose’s RuneQuest that didn’t actually depend on the OGL and SRD. Since the trademark returned to Moon Design, they’ve published their game as Mythras (2016).

Sceaptune (2007). An example of one of the many publishers who appeared to produce Mongoose RuneQuest products, then disappeared shortly thereafter. Sceaptune is particularly notable because they didn’t just publish one-off rules or adventures (like many), but instead produced their own Lost Isles setting as well as a few books on ducks. Some of their books also made it into print, whereas a lot of OGL publishers were PDF-only. Following the end of their RuneQuest line in 2009, they tried a Mongoose Traveller publication in 2010, before closing up shop.

The One-Off Publishers

A few one-off publishers don’t appear on the chart because their entries would be a single square. Nonetheless, they produced some very interesting products!

Darcsyde (2001): A one-off licensee who published the Elric! supplement Corum (2001), after Chaosium had otherwise shut the line down.

Wizards of the Coast (2002): Chaosium licensed Wizards of the Coast to publish the d20 Call of Cthulhu game (2002), which was in turn partially designed by Pagan Publishing. Wizards also has numerous other connections, spreading like a spider web. When they hired John Tynes, it was what caused Pagan to move (and thus Biohazard Games to form). They later offered Tynes the Everway game (1994) before it went to Rubicon Games and later Gaslight Press. Several companies on the chart (including Chaosium, Fantasy Flight, and Mongoose) have taken advantage of Wizard’s d20 license, and finally, Wizards now runs the Avalon Hill division of Hasbro.

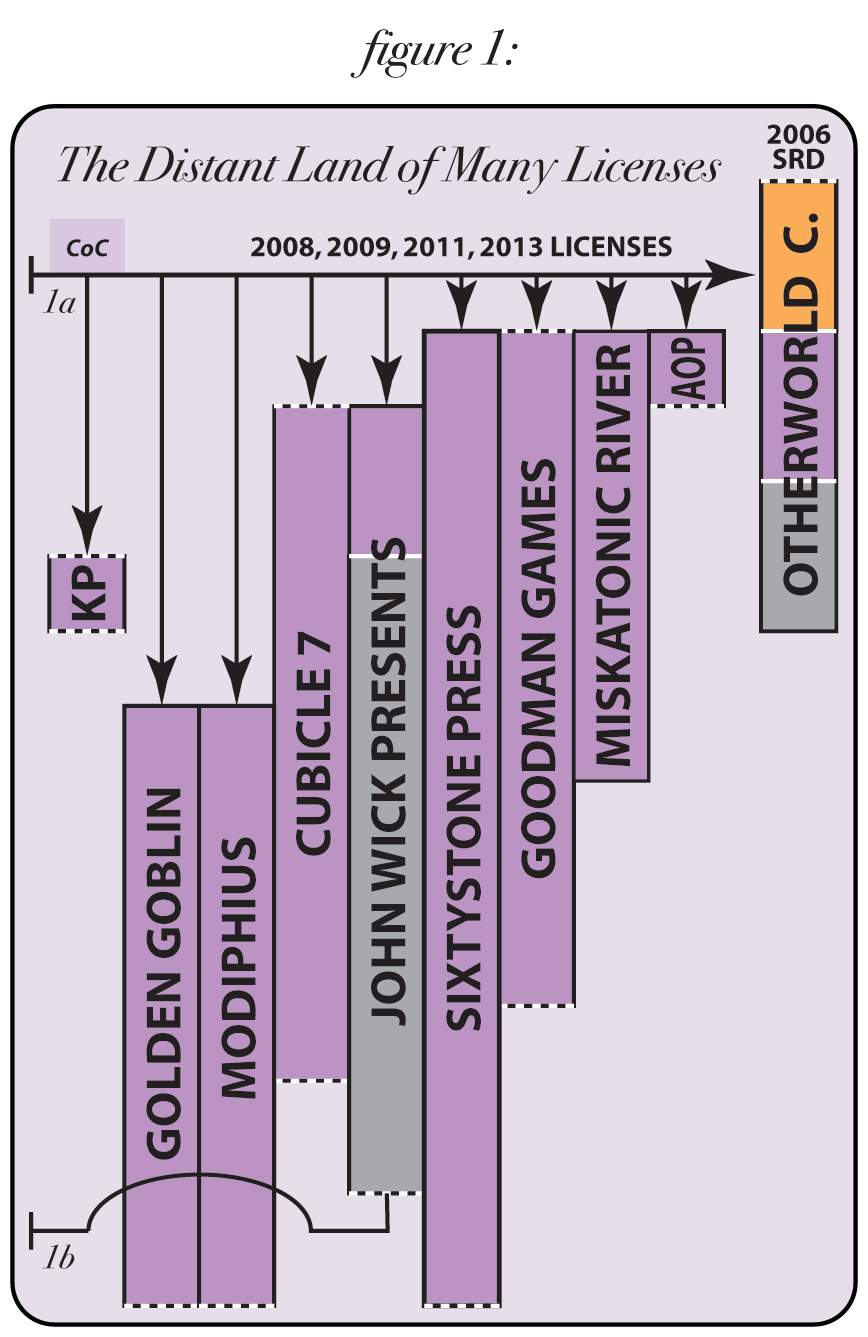

The Proliferation of Cthulhu Licenses

In the ’00s, Chaosium was barely hanging in there financially. This is one factor that led to the proliferation of Cthulhu licenses in the late ’00s and early ’10s: Chaosium was willing to give out licenses for no cash, just requesting printed copies of the products that they then could sell in their own store. Another factor was the easy accessibility of PDF publication. Given those two elements, third-party Cthulhu products multiplied, and though there was no Pagan Publishing—level publisher, the quantity of products may have overshadowed what little Chaosium was able to put out at the time.

Though a few of these companies are Call of Cthulhu-specific, many more of them tried out Cthulhu supplements as part of a larger publishing plan.

Atomic Overmind Press (2008). Producer of a few books by Ken Hite.

Cubicle 7 (2009). A prolific, multifaceted publisher. They produced Cthulhu Britannica supplements (2009-2015), a World War Cthulhu line (2013-2017), and a BRP-based Laundry Files game (2010-2015) before they turned to focusing on other things.

Golden Goblin Press (2013). A publisher of Call of Cthulhu adventures, settings, and other supplements that feels very in-tune with Chaosium’s production of the ’80s. Includes the newest edition of Cthulhu Invictus (2018), previously published by Chaosium.

Goodman Games (2008). Created an “Age of Cthulhu” line of adventures.

John Wick Presents (2009). Published a few “Yellow Sign” related adventure PDFs. Years later, Wick sold his 7th Sea game to Chaosium and joined the company.

Kobold Press (2011). A D&D-focused company who published Red Eye of Azathoth (2011).

Miskatonic River Press (2008). Keith Herber’s company for Call of Cthulhu adventures. Unfortunately, it slowly faded after his passing.

Modiphius Enterthave numeainment (2013). Perhaps the most successful of the modern Call of Cthulhu licenses. They got their start with Achtung Cthulhu! (2013), and have moved on to being one of the most notable new companies of the ’10s. They also have numerous connections to the Swedish gaming industry ultimately created by Chaosium’s properties.

Otherworld Creations (2006). A long-lived company that supported a lot of licensors over the years. They put out a few of the earliest books under the Mongoose OGL, primarily supporting their Diomin setting (2006) and then moved on to a year or two of well-received Cthulhu supplements before heading over to Pathfinder.

Pelgrane Press (2007). Technically not a license. When Pelgrane released Trail of Cthulhu (2007) for GUMSHOE, it was under an “agreement” with Chaosium, which means that Chaosium wanted to keep their toe in the water as the licensor of all things Cthulhu. Pelgrane later granted “permission” for Chaosium’s 13th Age Glorantha (2018).

Sixtystone Press (2008). An infrequent publisher of supplements, most notable for their Lost in the Lights adventure (2013, 2017) and their support of Yog-Sothoth.com’s Masks of Nyarlathotep Companion (2017).

The Return Home

By the late ’00s, Chaosium was a shadow of its former self. Pendragon was gone to Green Knight, RuneQuest and Glorantha were gone to Issaries. Even Stormbringer had been traded away by reverting the license to Michael Moorcock so that Mongoose could license it themselves. Chaosium had Call of Cthulhu and their core BRP system and little more.

What’s amazing is that after the company came under new management in 2015, the new team then proceeded to get the band back together.

The story of Pendragon’s return to Chaosium is simple: Peter Corless sold the rights to White Wolf, and then when Stewart Wieck left White Wolf to form Nocturnal Media, he took Pendragon with him. He shepherded the game for several years, and later stated working with the revamped Chaosium; after his passing, the game returned to Chaosium.

The story of the return of RuneQuest and Glorantha begins with one other cast member:

Reaching Moon Megacorp (1989). A fan organization that started publishing when RuneQuest was under the control of Avalon Hill. As Avalon Hill first paused and then ended Gloranthan RuneQuest publication, Reaching Moon became the carrier of the RuneQuest flame, lighting the darkness when the line might otherwise have died out in the ’90s. They were a crucial member of the continuation of the line.

Meanwhile, Issaries was able to combine its Gloranthan rights with a returned RuneQuest trademark and its own HeroQuest game, unifying all those rights for the first time in decades. They then passed them on to Moon Design, themselves a spinoff of Reaching Moon, and in time Moon Design came to control Chaosium.

Today Chaosium is complete for the first time since 1984, minus the rights to Michael Moorcock’s Eternal Champion.

New Cthulhu Licenses

Following its reorg, the new leadership of Chaosium has allowed some Cthulhu licenses to continue, but they’ve also begun new licensing more thoughtfully:

Darker Hue Studios (2017). The publisher of the gold-ENnie award-winning Harlem Unbound (2017) that Chaosium themselves published in a second edition (2020).

New Reverse Licenses

The newer incarnation of Chaosium has also licensed one more game system, just like they did with Nephilim decades earlier.

Rob Heinsoo Games (2018). Rob Heinsoo Games (and previously Fire Opal Media and/or Fire Opal Games) owns the right to the 13th Age game system that’s the heart of 13th Age Glorantha (2018) as well as Pelgrane Press’ 13th Age (2013).

Final Notes

This article outlines 72 (or so) different companies that interacted with Chaosium, almost all of whom benefited from Chaosium’s properties in one way or another. Though Chaosium has at times been small, their effect on the industry as a whole is quite large (and that surely misses dozens of more distant connections).

It’s quite possible that only TSR (through its creation of the industry) and Wizards of the Coast (through the OGL) have interacted with more companies.

And with Chaosium newly revived and producing more and better material than they have in decades, and with almost all of their properties returned home for the first time since 1984, it’s quite possible that they may have a new golden age of connections before it.

This article was originally published as Advanced Designers & Dragons #34 on RPGnet. It followed the publication of the four-volume Designers & Dragons (2014) from Evil Hat, and was meant to complement those books.