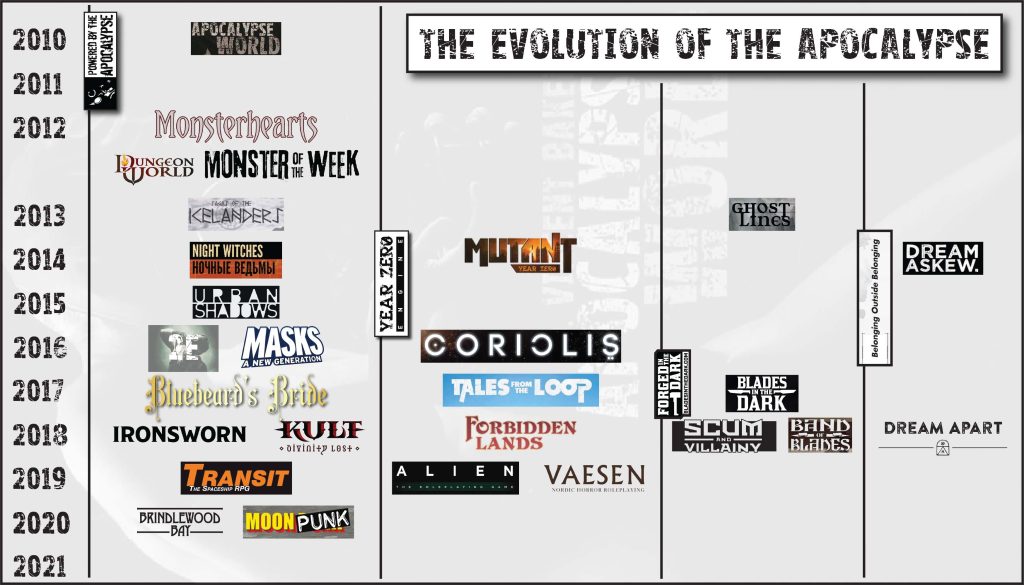

n 2010, Vincent and Meguey Baker released Apocalypse World (2010), which trailblazed a new generation of indie roleplaying development. Its success was in in part because the Bakers invited other designers to create their own games that were “Powered by the Apocalypse”. However, Apocalypse World was more than just a new game system. It was a new sort of game, or to quote Vincent Baker: a new “approach to system design”. When later games adopted Apocalypse World designs, they were sometimes hacking its mechanics directly, but the more far-flung variants instead hacked its design approach, sometimes with entirely new mechanics.

Apocalypse World (2010). Apocalypse World is a post-apocalyptic RPG, but it’s a far cry from classics such as Gamma World because it reimagines player actions, GM actions, and the whole idea of success, and it does so by going back to the origins of the roleplaying industry and focusing on roleplaying as a conversation between participants.

- Player Moves. Player actions focus on “moves”, which are specific actions with well-defined results. The result is great genre emulation: characters do the things and get the results that you’d expect within a genre. It also differentiates character roles and makes them genre-appropriate (while also creating niche protection, though that was largely accidental: Baker didn’t want gamemasters to have to bring along multiple copies of each playbook, so he created the limit of one of each role in each game). This could have created a game-y system, but the Bakers instead linked it back to the narrative focus so prevalent in indie games by requiring players to describe what they were doing, and to only trigger a move through proper description.

- Partial Success. All actions in Apocalypse World can result in one of three levels of success: failure, success, or partial success — with partial success being the most common sort of success. This not only adds more nuance to each resolution, but also creates the constant possibility of “success with complication”, adding fuel to the storytelling.

- GM Agendas. GMs (or MCs) in Apocalypse World are treated just like another player. They have no preconceptions as to where the plot is going, and their actions are codified as moves just like those of the players. This is paired with the innovation of making the game player-facing: the GM doesn’t do any die-rolling, leaving the active actions in the game to players, ensuring they’re the true drivers of the story. That’s not to say that the GM doesn’t have a responsible creative role in Apocalypse World. The game contains Agendas and Principles that the GM works to integrate into the game. Though introduced by the GM, these ideas focus on the characters, with two of the core Agenda items being “make the players’ characters’ lives not boring” and “play to find out what happens”.

Following the release of Apocalypse World, many designers “hacked” the system to support their preferred genres of play, but some hacks diverged to become their own categories.

Year Zero (2014). Tomas Härenstam melded indie game mechanics with traditional game design in his “neotrad” Year Zero system, which debuted in Mutant: Year Zero (2014). The resultant games aren’t exactly “Powered by the Apocalypse”, but they’re at least “Heavily Influenced by the Apocalypse”. Evocative fiction-first skills push the narrative forward; characters have tightly linked relationships; and the GM is given a set of events to introduce complications to the game, as well as a set of principles for evoking post-apocalyptic play. Three of those principles are straight out of the Apocalypse World playbook, reminding the GM that “The players lead the way”, “The players have the answers”, and “The end is never set.” The GM actually makes rolls in Mutant: Year Zero, but this isn’t true in some later versions of the system, such as Tales from the Loop (2015), which returns to the player-facing design of Apocalypse World.

Blades in the Dark (2017). John Harper started his Apocalypse World design with Ghost Lines (2013), a “hack” of the original game. Blades in the Dark continues with the same setting, and is still obviously a descendent of Apocalypse World, but is somewhat more far-flung. The “actions” continue to be unique genre-defining and class-defining skills, just like Apocalypse World‘s moves, though they can be somewhat broader in actual usage. They also continue to allow partial success, but with a different die mechanic: a pool of d6es are rolled and the highest roll determines full (6) or partial (4-5) success or failure (1-3). Finally, much as with Apocalypse World, the GM has familiar sounding goals such as “convey the fictional world honestly” and (of course) “play to find out what happens” — as well as their own list of actions and their own principles. Like Apocalypse World, the “Forged in the Dark” games are player-facing.

No Dice, No Masters (2019). The big mechanical variation in the No Dice, No Masters system, used in Dream Askew / Dream Apart (2018) and other games, is that (as the name suggests) there’s no randomization and no gamemaster (MC). Instead, players take on the roles of setting elements in addition to their characters, dividing up the GMing. The idea of partial success is then maintained with a token economy: players can make weak moves (which might make them vulnerable) to gain a token or strong moves (which allow them to shine) at the cost of a token. It’s a clear demonstration of why Baker called Apocalypse World an “approach”: designer Avery Alder maintained that approach while changing up the actual mechanics.

This article was originally published as Advanced Designers & Dragons #58 on RPGnet. It was purposefully written for publication in the next generation of books, most likely in one of the Apocalypse-related histories in Designers & Dragons: The ’10s.