It’s been 15 years now since the Dragon was killed by the Wizards on the Coast, following the golem’s publication of issue #359 in September 2007. But we nonetheless remember its birthday, which was June 1976, 46 years ago this month.

The previous four articles in this series looked at the cover art of Dragon over the first two years of its publication. Now, entering its third year, Dragon has become more professional and (at last!) committed to a monthly publishing schedule. From here on, it wouldn’t miss a month until 1997.

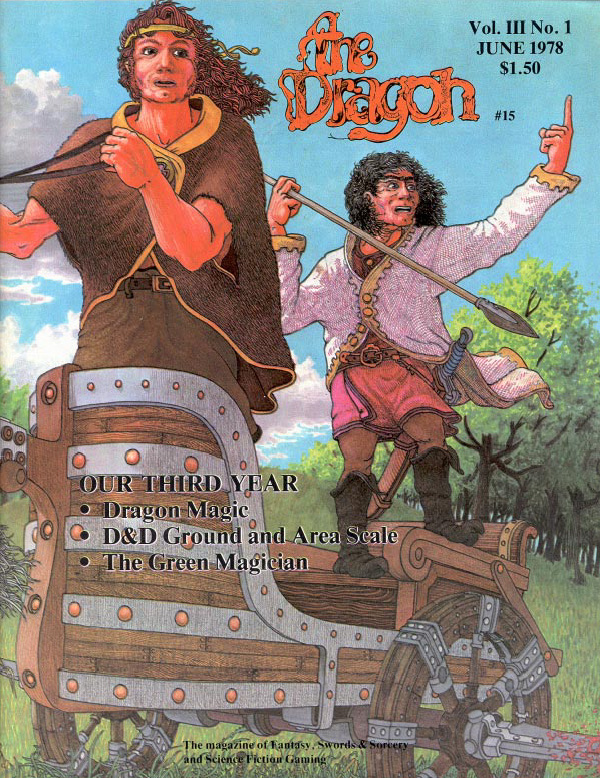

The Dragon #15: Dave Trampier (June 1978)

There’s no dragon on the cover of The Dragon’s second anniversary issue, but it in fact would be several years before dragons became common-place on the anniversary covers. Instead we get an illustration of two Celtic fighters in a war chariot. This image was drawn for “The Green Magician”, a “Harold Shea” story authored by L. Sprague de Camp, the first part of which was contained within. Depicted on the cover are charioteer Laeg mac Riangabra and spear thrower Cuchulainn the Mighty from the story, making this a major Irish mythology cameo. Note that the illustration continues onto The Dragon’s back cover, perhaps the only such double-page cover-spread in the magazine’s history.

Publication of the story wasn’t a coup like much of The Dragon’s early fiction publication, because it was a reprint of a story originally published in Beyond Fantasy Fiction #9 (November 1954) and then later reprinted in Wall of Serpents (1960). Nonetheless, it was likely hard to acquire at the time as this and the final Shea outing were inexplicably left out of The Compleat Enchanter (1975), though a number of smaller press publications of those stories appeared starting in 1978. In any case, printing the story demonstrated not just The Dragon’s continued commitment to fantasy fiction, but also to stories that would soon be referenced in “Appendix N” of the Dungeon Masters Guide (1979):

de Camp & Pratt. “Harold Shea” Series; CARNELIAN CUBE

Even more notable is the artist: Dave Trampier. Trampier was one of the earliest members of the TSR Art Department, whose work could be found throughout the AD&D rulebooks alongside illustrations by Dave Sutherland and others. Many of them are considered iconic, such as his adventurers looking into a treasure chest in the Monster Manual (1977) and his “Emirikol the Chaotic” from the Dungeon Masters Guide (1979). Trampier’s black and white art had a maturity and depth to it that made it stand out in AD&D’s early products. He’s also, of course, famous for the full-color idol-looting cover of the Players Handbook (and for many other pieces).

Trampier had also formed his own connection with TSR Periodicals through the creation of his comic strip, “Wormy”, which had begun running in The Dragon #9 (September 1977); it told the story of a dragon and the goblins and other monsters that were most typically adversaries in D&D games. This was likely the connection that led to Trampier drawing a Dragon cover, as he was just the second artist from TSR’s artistic bullpen to do so, after Dave Sutherland’s cover for The Dragon #5 (March 1977).

The later story of Dave Trampier has always lay somewhere between mystery and tragedy. He continued working at TSR into the ’80s and even after that “Wormy” continued at Dragon through #132 (April 1988). It was then abruptly cut off in the middle of a storyline, with plans for a graphic-novel collection left unfulfilled. Trampier didn’t just withdraw from the gaming community: he disappeared. He was rediscovered as an Illinois taxi driver in 2002, but still had no interest in the gaming community until late 2013, when Yellow Tax Company went out of business. He had accepted an invitation to attend a local game convention called Egypt Wars, where he was to display his artwork, but then he passed on March 24, 2014 shortly before the convention.

Nonetheless, early Dragon magazines and TSR products remain as a permanent testament to his artistic ability.

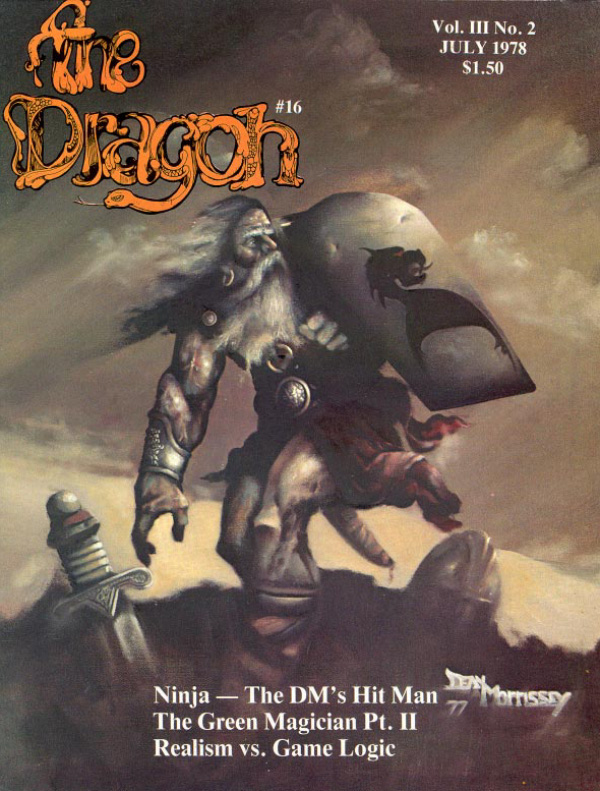

The Dragon #16: Dean Morrissey (July 1978)

The cover for The Dragon #16 is the work of Dean Morrissey, one of the new artists brought in by Tim Kask for interior work a few issues earlier, now upgraded to a cover. Morrissey was a self-taught artist from Boston who got his start with his Dragon magazine interiors and covers: he’d produce numerous covers for the magazine over the years. He also worked across the roleplaying and boardgaming industry, including producing well-known covers for the Borderlands boardgame (1982) and Cosmic Edition Big Box Edition (1982), both by EON. By the ’80s he was also producing genre book covers, and by the ’90s he was illustrating his own children’s books, the first of which was Ship of Dreams (1994). Morrissey passed on March 4, 2021.

Morrissey’s cover for The Dragon #16 doesn’t look like that of a newcomer to the field: it instead showed the increasing professionalism that The Dragon was enjoying. Here, a warrior walks across a gray battlefield, looking to recover his sword and helmet (or perhaps abandon them). The style is clearly influenced by Heavy Metal artists such as Richard Corben, as seen by the over-muscled and veiny nature of the warrior’s thews. One would like to think that the warrior is the grim Irish hero Cuchulainn from “The Green Magician”, which concludes in this issue, but there’s no scene that’s a direct correlation. (But as it turns out, Morrissey’s covers would have an interesting relation with their source material, if his next outing was an example.)

Meanwhile, the fiction in The Dragon was apparently causing some controversy, as Tim Kask wrote in an editorial in this issue about “Philistines” who didn’t want to see any stories. He even had to note that four pages were added to The Dragon #16 to accommodate the length of De Camp’s finale to “The Green Magician”, something done “to forestall the howls”. Kask concluded his commentary on the fiction that was ever-present in The Dragon’s early years (and so frequently depicted on the cover) with the statement: “It has always been THE DRAGON’s contention that roleplaying gaming requires large amounts of stimulation to ensure fresh and viable campaigns. Due to the fact that virtually all of the good roleplaying games require liberal interpretation, fresh ideas are paramount. We will continue to bring you quality heroic fiction.” (It would still be another year before the publication of the “Inspirational Reading” list in the Dungeon Masters Guide.)

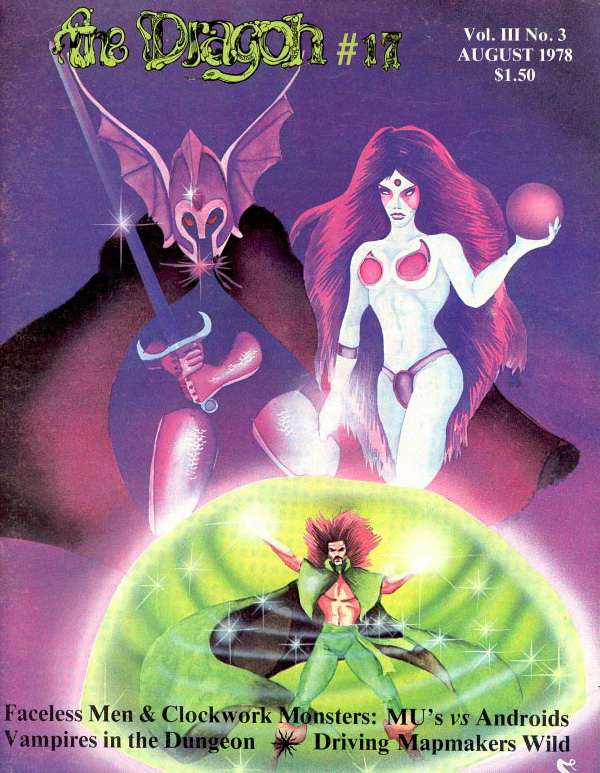

The Dragon #17: John Sullivan (August 1978)

For some reason, The Dragon stopped giving credit to its cover artists in its third year. Thus, we only know that the cover to The Dragon #17 is by the mysterious John Sullivan because it’s properly credited in The Art of Dragon Magazine (1988), though educated guesses could have been made about the artist thanks to his continuing use of very vibrant colors, which stand out against some of The Dragon’s more neutral covers. Sullivan had previously offered up the demon-summoning cover to The Dragon #10 a year earlier.

Just like its predecessor, this is a pure swords & sorcery cover (or more properly, sword & sorceress). An evil-looking warrior and his nearly-nude female companion advance toward a spell-casting wizard who might be a member of a hair metal band. The perspective is wonky. Perhaps the wizard is actually in a crystal ball? Or maybe he’s been shrunk with a spell? It’s unclear. Obviously, some of The Dragon’s covers were still running at the semi-professional level that was so common in the industry’s early years.

The cover illustration doesn’t seem to have any particular relationship to the content of the magazine, which Kask calls “a potpourri”, though this there’s an article inside by James Ward about magic-user variants. (Most notably, there’s no fiction, which was so often the tie-in to the cover art.)

Many of us see the iconic character Warduke in the illo, but there’s no known connection between this cover and the later character design by Tim Truman.

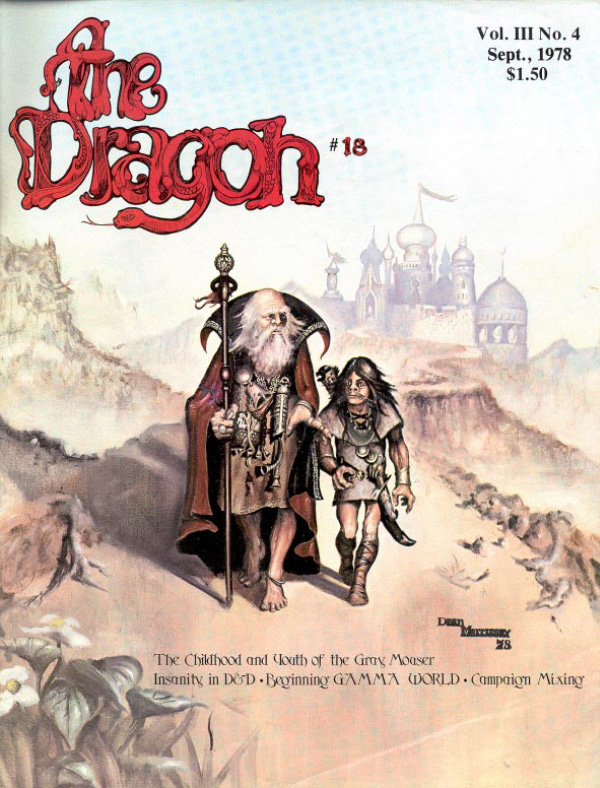

The Dragon #18: Dean Morrissey (September 1978)

Just two months later, Dean Morrissey was back for a return appearance. Like its predecessor, this new cover feels like it should be connected to the fiction inside, which is “The Childhood & Youth of the Gray Mouser”, by Fafhrd & Gray Mouser co-creator Harry Fischer, also the author of previous Dragon story, “The Finzer Family”. Within, the story tells about Mouser’s youth, including his apprenticeship to “old and twice-failed sorcerer” Glavas Rho. That certainly seems like what is depicted on the cover. To be precise, it seems to be the Mouser and Glavas Rho leaving Lankhmar via the Great South Gate, an event from the story.

Sort of.

The problem is that Mouser is depicted by Morrissey with a cat’s whiskers and eyes!

This was probably an issue with commissioning art from someone not as closely associated with TSR or the RPG field, an issue that would grow as The Dragon approached the ’80s, when it would increasingly lean on mainstream fantasy artists rather than the local and roleplaying artists of its youth. For now, though, The Dragon had its second Fafhrd and Gray Mouser cover, following The Dragon #11 (December 1977). Probably. And it was a uniquely science-fantasy take on the Two Who Sought Adventure: the world of Nehwon as seen through the lens of Heavy Metal.

The story, by the by, was another of The Dragon’s most notable. Though it wasn’t by Fritz Leiber, who wrote the rest of the twain’s adventures, it was an official, never-before-seen story about The Gray Mouser. Even moreso, The Dragon remained the only place to find it for a long time. Fischer’s story was only included in one of the main Fafhrd & Gray Mouser collections in the limited-edition Centipede Press edition of Swords & Deviltry (2017), almost four decades later — with no other publications appearing in between!

The Dragon #19: Dale Carlson (October 1978)

The muddled cover of The Dragon #19 looks like it’s probably depicting a dragon, and that’s largely confirmed by the fact that The Art of Dragon Magazine (1988) places it in the “Dragons” section of the book. But beyond that, this is the most “modern” art to ever appear on the Dragon cover. Perhaps it’s a dragon’s head being formed out of fungus? Or maybe it’s fungus colonizing a dragon, living or dead? It’s really not clear, which is what makes this piece entirely unique in the history of Dragon magazine.

It’s a bit of a pity that this was used as the October cover rather than the June cover, but Dragon hadn’t yet solidified its traditions of depicting dragons in the summer and undead in the fall. Though TSR had already flirted with anniversary dragons on the covers of The Dragon #1 (June 1976) and The Dragon #7 (June 1977), its first Halloween issue would actually appear in a month, cover-dated November 1978!

Since Dragon wasn’t properly crediting all of its cover artists in its third year, we only know of the name Dale Carlson from The Art of Dragon Magazine. He’d go on to supply the artwork for four months in the Days of the Dragon 1980 Calendar, alongside other Dragon mainstays such as Ellrohir, Phil Foglio, and Dean Morrisey, and then a single month in the 1981 calendar, plus one more Dragon cover … and that’s all we know about him. He’d disappear after his Dragon-oriented work from 1978-1980.

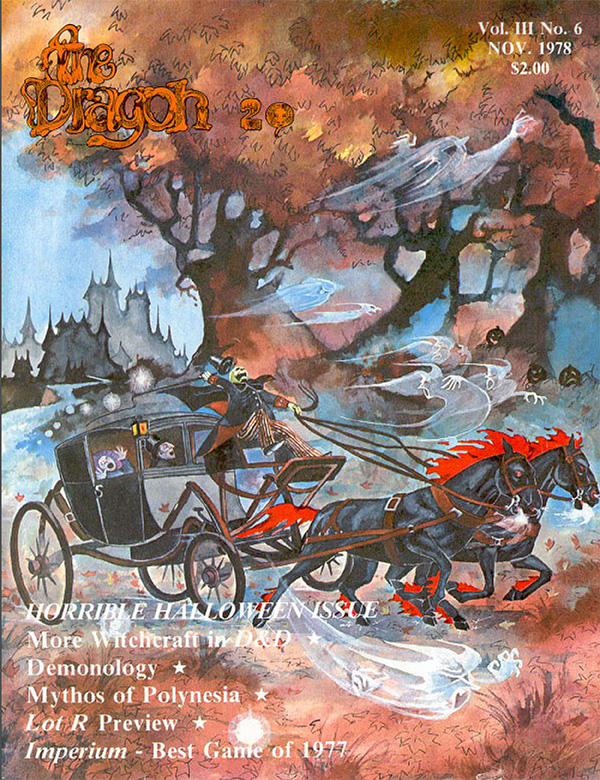

The Dragon #20: Elrohir (November 1978)

A month late, The Dragon #20 ran the magazine’s first Halloween-focused cover, called “Ghosts”. It’s an image of a demonic carriage escorted by spirits. Perhaps more notably, this was TSR’s first real horror cover, unless you count the implied sacrifice on Supplement III: Eldritch Wizardry (1976). Like the anniversary dragons, it would take a few years for Halloween covers to become a regular tradition.

Equally importantly, this was just the second official theme issue for Dragon following on from the Empire of the Petal Throne special in The Dragon #4 (December 1976). This time around, it’s a “Horrible Halloween Issuee”, supported by articles on “Witchcraft in D&D”, “Demonology Made Easy”, and “Demonic Possession in the Dungeon”. One can’t imagine seeing articles like that just a few years later, after moral minority groups began hunting for actual satanism in D&D. Really it would be hard to imagine these articles appearing in any other period in the game’s history. But in late 1978, D&D was just edging into professional publication, and so dark magic was still acceptable. However, the clock was ticking: it’d be less than a year before James Dallas Egbert III disappeared from his dorm room at Michigan State University, leading to the first lies about D&D appearing in the mass-media; not long after that, D&D became a target of the Satanic Panic, which would definitely preclude articles of this type in the future.

The use of a theme issue as the topic for cover art marked a real milestone in The Dragon as it was in the process of transforming from being a fiction-and-gaming magazine to a pure gaming magazine. In fact, the next fiction wouldn’t appear until The Dragon #23 (March 1979), which would see the return of Gardener Fox and Niall (though there’d still be plenty more fiction in the magazine, and some of it would still be cover featured).

This cover is by Elrohir, which is to say Ken Rahman, who had previously provided the covers for The Dragon #7 (June 1977), The Dragon #11 (December 1977), and The Dragon #12 (February 1978). Like his best works, this one featured sophisticated shading, likely the result of water colors. It represented the continuing sophistication of The Dragon’s cover art in its third year.

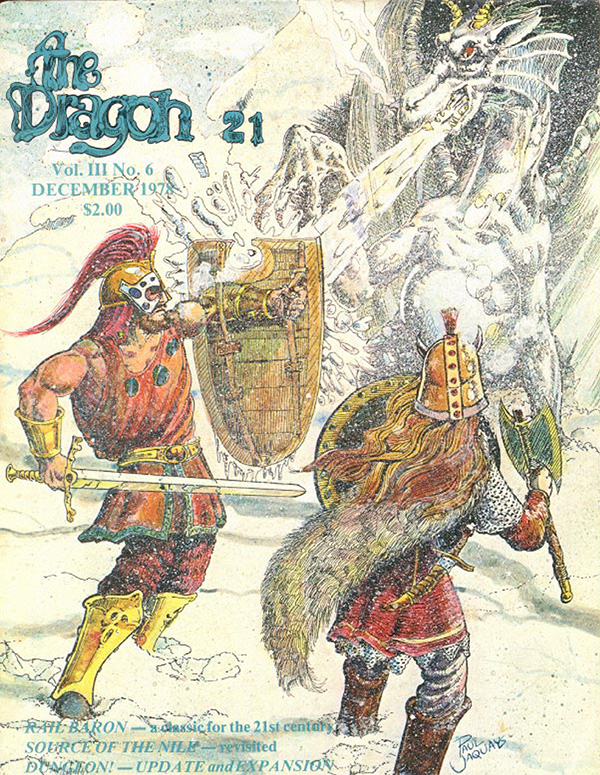

The Dragon #21: Jennell Jaquays (December 1978)

The cover of The Dragon #21 is very appropriate for the winter season. In fact, when Tim Kask purchased it, he noted that it’d be perfect for the December or January issue. The painting shows a white dragon assaulting adventures in a frozen landscape, complementing the green (#1), red (#7), and moldy yellow (#19) dragons seen on previous covers. The art is by Jennell Jaquays.

Jaquays got her start in gaming at Spring Arbor College in Michigan, where she and Mark Hendricks founded the Fantastic Dungeoning Society and their adventure magazine, The Dungeoneer (1976-1981). Its first issue (June 1976) was published the same month as both The Dragon #1 (June 1976) and Wee Warrior’s Palace of the Vampire Queen (1976), and thus like those other publications, it was groundbreaking: both as an FRPG periodical and a book of FRPG adventures.

As she approached graduation, Jaquays didn’t have any time left to spend on The Dungeoneer, so she sold it to Chuck Anshell, who would bring it with him to Judges Guild. This cover art was then created by Jaquays in the spring of 1978 for her Senior Art Show, while she was finishing up her last semester of college. She submitted it to The Dragon afterward as a slide, and when Tim Kask accepted it, she forwarded along the original — which is how things were done at the time. (Jaquays still has the receipt: she was paid $60 for the cover, which reveals the payment rate for these early issues of the magazine. That’d be about $250 today.)

By the time “Ice Dragon” ran on the cover of The Dragon, Jaquays was working at Judges Guild herself as an artist. She’d gain increased renown in the RPG field over the next few years as the author of The Caverns of Thracia (1979), Dark Tower (1980), and others. So while the piece might look like a major change for The Dragon, as if they’d started picking up cover artists from elsewhere in the gaming industry, at the time Jaquays’ Dungeoneer magazine was just becoming more widely known thanks to The Dungeoneer: The Adventuresome Compendium of Issues 1-6 (1979) from the Guild. So, much like The Dragon’s other early artists, Jaquays was just breaking into professional work — and much like some of the other artists of the magazine’s third year, her cover work was preceded by interior black and whites, in Jaquays’ case, a wizard in The Draogn #1.

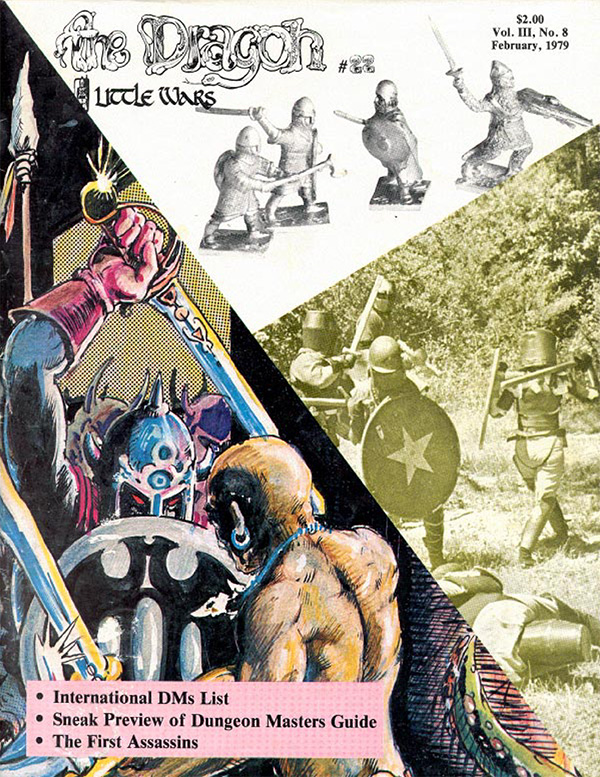

The Dragon #22: Steve Swenston (January 1979)

The Dragon opened 1979 with a real mishmash of a cover, compositing two photographs (one of fantasy miniatures battling, another of fantasy reenactors doing the same) with a drawing by Steve Swenston of yet more fighting. The concept is pretty cool, showing the evolution of gaming across miniatures warfare, live-action roleplaying, and tabletop roleplaying, but the composition is crude.

The reason for the composition was to demonstrate that Little Wars (1976-1978), TSR’s miniature wargaming magazine, was combining with The Dragon. Thus, The Dragon #22 was technically also Little Wars #13. The experiment apparently didn’t go well because this was the last time Little Wars was ever heard of. The next issue would drop the extra content — and also the 20 or so extra pages that came with it. If The Dragon #20 had suggested that the magazine would be slowly backing off of its fiction content in favor of pure roleplaying articles, The Dragon #22 (and the lack of followup in future issues) pretty decidedly showed that roleplaying games were steamrolling over the wargames that had begat them.

Steve Swenston, like Jennell Jaquays before him, had already done some work in the industry when his work was selected for use on the cover of The Dragon, but nothing at the time that was mass-market enough that the average D&D player was likely to have heard of him. In Swenston’s case that was the cover artwork for the original release of White Bear & Red Moon (1975), Greg Stafford’s wargame of fantasy warfare in the world of Glorantha.

Swenston had actually come into roleplaying via Wyrd (1973-1977), a fanzine of illustrated fantasy. Stafford had come aboard as Assistant Editor and Swenston as Art Editor with issue #4 (1975), the issue that moved Wyrd from its Michigan birthplace to California. When Stafford decided to found Chaosium based on a successful Tarot card reading, he brought with him two artists from Wyrd, William Church and Steve Swenston, who then provided art for Chaosium’s debut release, White Bear & Red Moon. They even got to name some of the previously untitled cities in central Glorantha: Church named Wilm’s Church and Swenston Swenstown.

The Dragon #22 was Swenston’s first step into the wider world of roleplaying art, before he did some of his more notable color work for Chaosium, such as Cults of Prax (1979) and Different Worlds #1 (1980). He’d go on to produce a few more covers, and even a very brief Dragon comic strip and has done scattered work on comics and children’s books as well.

One of themost interesting aspects of Swenston’s illustration is the use of Zipatone (or more generally: screentone, but Zipatone is what everyone called it). That’s the dotted pattern found behind the purple-and-blue swordsman. Zipatone was a dry-transfer texture. You placed it on an illustration, rubbed it with a stylus, and voila you had a textured pattern without the difficulty of stippling or hatching. Judges Guild was the roleplaying publisher that used it the most frequently, probably because many of their drawings were made to be printed either black & white or color, but here it was on a Dragon cover. Obviously, the use of screentone is almost entirely history nowadays, since that sort of pattern can be easily created on a computer, even if the original art wasn’t drawn there (but often it is).

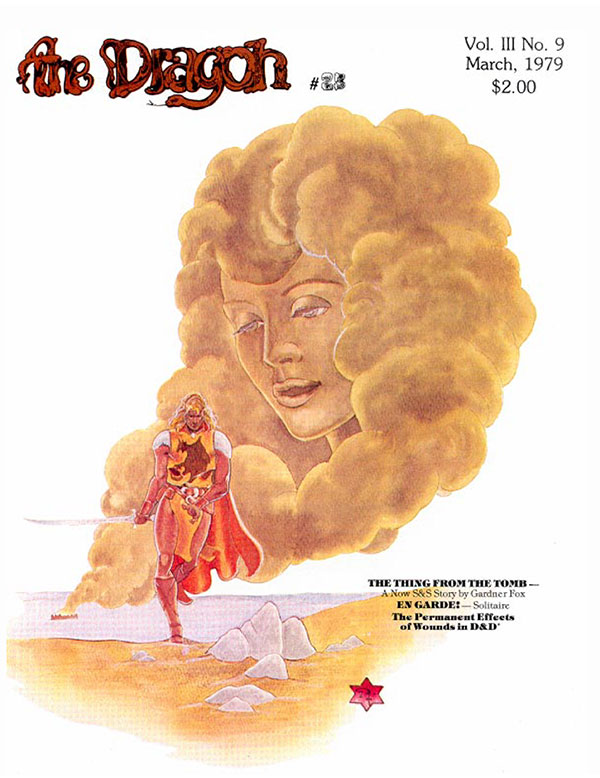

The Dragon #23: Artist Unknown (February 1979)

There are two interesting elements to the cover for The Dragon #23, which depicts a blonde crusader walking across a sandy beach with some sort of sandy phantasm rising up behind him.

The first is that we don’t know who the artist is, despite the fact that there’s a very ornamental signature, depicting what looks like a whip or a scythe in a six-pointed star. Closer inspection suggests it could be a “3T” or even a “CT the third”. But the artist wasn’t credited in The Dragon, as was the case throughout the third year, nor in The Art of Dragon Magazine (1988), which reveals most of the secret artists of the early Dragons. Tim Kask also doesn’t have any idea as to who the artist might have been at this late date.

The second is that the art features the early Dragon’s most recurrent cover model: Niall of the Far Travels. The weird thing is that he looks totally different from his earlier appearances. The Dragon #2 (August 1976), The Dragon #5 (March 1977), and The Dragon #13 (April 1978) all depicted Niall as a dark-haired barbarian. But here he’s blonde and looking much more civilized. If there’s any doubt, the same (mystery) artist depicts him just the same in black & white art inside. Perhaps Niall has simply come up in the world, as Conan did, for the text does describe him as now wearing chainmail and serving a king whose emblem is a basilisk. But the hair-color change can’t be explained so simply.

In any case, the fourth cover appearance of Niall revealed that Tim Kask was still interested in mixing pulp sword & sorcery stories with gaming materials, even if there had been a bit of a hiatus in the middle of The Dragon’s third year.

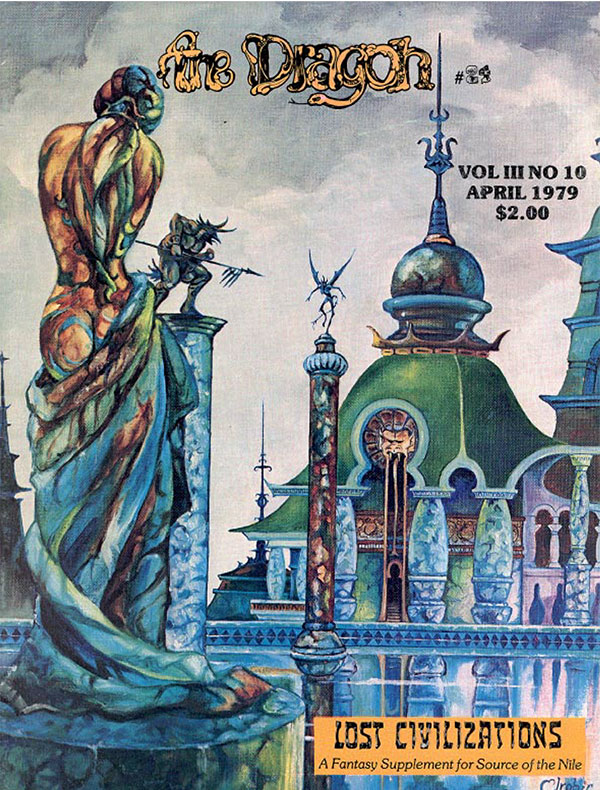

The Dragon #24: Elrohir (March 1979)

The next issue of The Dragon saw the return of Elrohir (Ken Rahman), marking his own fifth appearance on the cover of the magazine, following his Halloween-focused cover for The Dragon #20. This newest outing definitely shows off his typical style, featuring beautiful colors and shading, here depicting a somewhat monstrous fantasy city.

Though the cover of The Dragon had often featured black (or white) “cover lines” to advertise articles inside, a new style had appeared in 1979: colored boxes on the cover to break out those preview. Their debut was actually in The Dragon #22 (January 1979) but the compositional nature of that cover made it much less blatant. Here, the yellow block for the main cover line of “Lost Civilizations: A Fantasy Supplement for Source of the Nile” definitely makes it stand out, demonstrating how The Dragon was slowly pushing to more professional levels of design.

The actual “Lost Civilizations” article is by J. Eric Holmes, best known for his authorship of the first Basic Dungeons & Dragons rules (1977). One presumes that Kask purposefully matched a freelance piece of art with that article — as we know happened when Kask purchased Jennell Jaquays’ first cover artwork the previous year, then saved the wintry piece for the December issue. Having Elrohir provide the cover for a board-game feature was somewhat ironic, as his own Divine Right (1979) was fast approaching release from TSR.

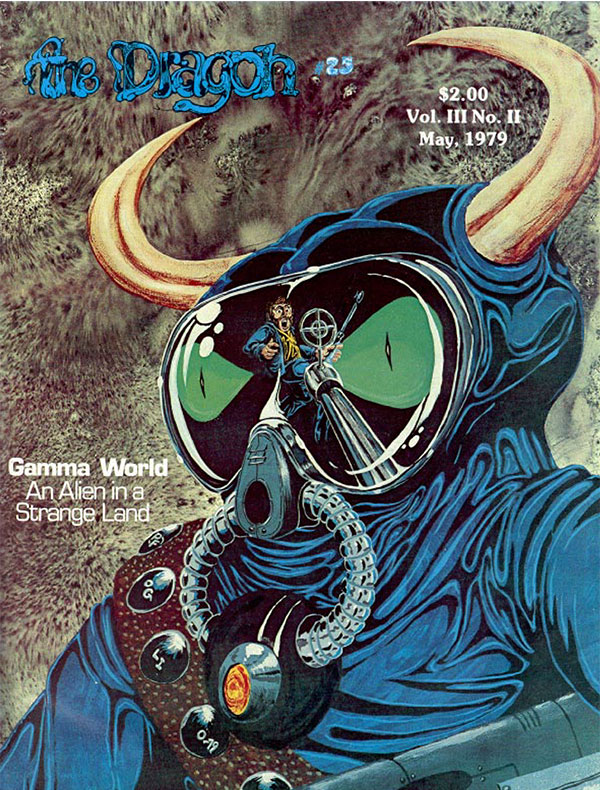

The Dragon #25: Phil Foglio (April 1979)

The cover for The Dragon #25 introduced one of the magazine’s best-known artists: Phil Foglio. Foglio had moved to Chicago to attend the Academy of Fine Arts in the mid ’70s. From there he became very involved in science-fiction fandom, winning the Hugo for Best Fan Artist in both 1977 and 1978. Though he wasn’t involved in roleplaying (and in fact wouldn’t play a roleplaying game until 1986), fandom in the Great Lakes era naturally brought him to Gen Con XI (1978) — or rather a friend who dragged him there did.

After beating Gary Gygax at a board game (and winning a copy), Foglio showed his portfolio to Tim Kask and also won a commission to do a cover for Gamma World (1978). The resultant cover is a mix of whimsy and seriousness, the former of which would be more common to Foglio’s future style. Here we get a survival-suited mutant with horns and weird eyes. His goggles show his next victim, being held at the point of a gun. It’s all against a weirdly textured background that’s the least cartoony part of the piece. (Foglio would be allowed to more fully embrace his cartoon style in his next Dragon cover.)

It had been almost a year since The Dragon’s last science-fiction cover, a relatively generic piece for The Dragon #14 (May 1978), and this was just the second time that the magazine had explicitly called out another of TSR’s games, following the EPT cover for The Dragon #4 (December 1976).

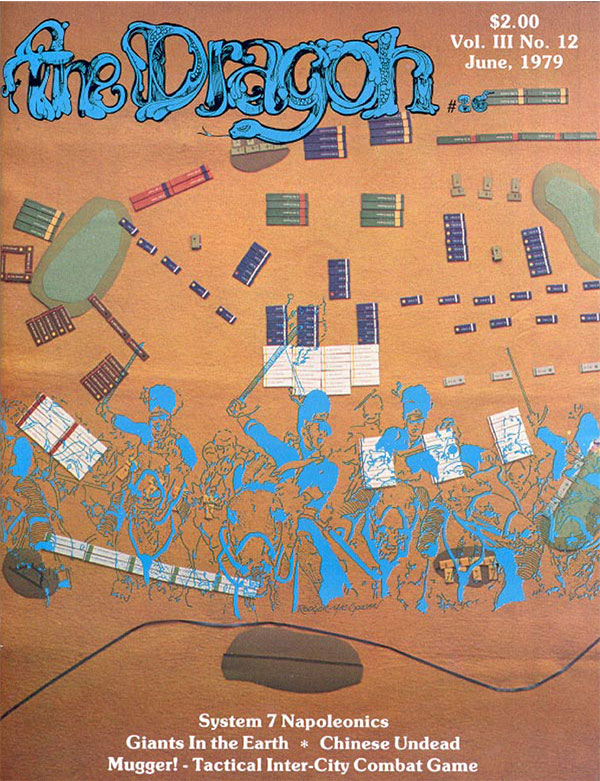

The Dragon #26: Rodger MacGowan (May 1979)

After almost a year of exclusive fantasy focus, from The Dragon #15 (June 1978) and its cover for “The Green Magician”, to The Dragon #24 and its depiction of “Lost Civilizations”, one might have thought that The Dragon had calcified as a D&D house-organ, despite Tim Kask’s efforts to maintain it as a magazine for the entire industry. But the end of year three reminded readers of the magazine’s expanded focus, first with Phil Foglio’s Gamma World cover and now on the year’s last cover with Roger MacGowan’s Napoleonic illustration.

It had been four months since Little Wars (1976-1978) had been incorporated into The Dragon and subsequently disappeared. Tim Kask, a miniatures wargaming aficionado, decided to give the topic one last try by presenting a trio of articles on System 7 Napoleonics (1978), a new game by GDW that replaced expensive miniatures with cheap cardboard counters for Napoleonic play.

The cover design, which shows battalions of counters facing off against each other, with imaginative Napoleonic legions rising up from that battlefield, is by Rodger MacGowan. Besides being the founder of Fire & Movement magazine (1976-2010), the legendary alternative to SPI’s Strategy & Tactics (1967-Present) and Avalon Hill’s The General (1964-1998), MacGowan was also a prolific artist. He would produce hundreds of pieces of cover art for over 20 wargaming companies over his career. Kask choosing him for this issue of The Dragon showed the seriousness placed on the wargaming topic.

Consider this the last gasp of wargaming, facing the onslaught of roleplaying. In fact, The Dragon’s depiction of any cover topics other than fantasy would also be at an end for the moment. From here on it was years of fantasy covers, broken only by the occasional modern comedy piece, mostly by Phil Foglio.

This article was originally published as Advanced Designers & Dragons #66-68 on RPGnet. It followed the publication of the four-volume Designers & Dragons (2014) from Evil Hat, and was meant to complement those books.