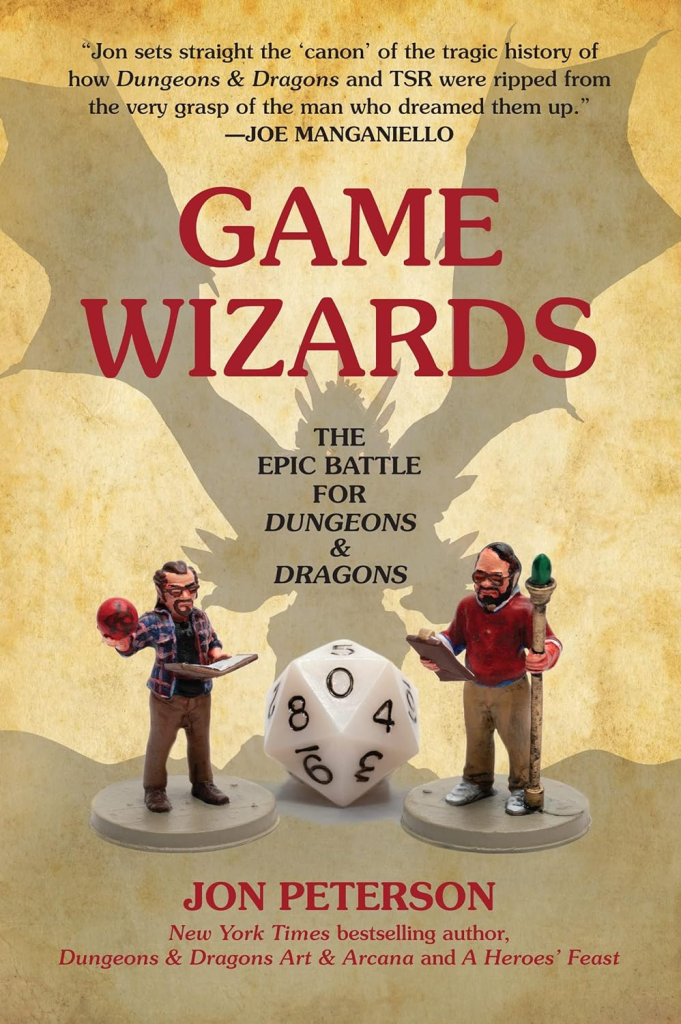

Jon Peterson was one of the leaders of the modern roleplaying history movement with his dense, academic, and insightful Playing at the World (2012). The Elusive Shift (2020) was somewhat more abstract, but Peterson’s third book is back in his original wheelhouse, detailing another history. Game Wizards (2021) tells the story of the aforementioned Wizards, including Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson, and their warfare that characterized the early industry.

The Contents of the Book

Game Wizards is arranged as a chronology in four parts:

- From a Club to a Company

- Adventurers in Business

- The Everfull Purse

- Disjunction

The first part is about the development of D&D and the foundation of TSR, while the next three parts each contain three-to-four chapters, covering one year of time each: 1975-1978; 1979-1982; and 1983-1985.

Although this book is rigorously academic, like its predecessors, it also takes a bit of time to have fun. Most notably, each year ends with “Turn Results” for the year, revealing revenue, employee count, and stock valuation for TSR, plus con attendance.

What We Learn About TSR’s Yearly Growth

Just those year-end turn results on their own offer a terrific insight into the ups-and-downs of TSR in its first decade.

Peterson’s compilation of these numbers is impressive. Even absent the considerable context offered in Game Wizards, they paint a clear picture of the initial rise _and fall_ of TSR.

| Year | TSR Gross | TSR Profit | Employees | GenCon Att. | Origins Att. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1975 | $60k | 5 | 1,000 | 1,500 | |

| 1976 | $300k | $19k | 10 | 1,500 | 2,200 |

| 1977 | $545k | $39k | 13 | 2,300 | 2,200 |

| 1978 | $930k | $58k | 19 | 2,000 | 3,400 |

| 1979 | $2.2M | $160k | 25 | 2,100 | 4,100 |

| 1980 | $8.3M | $1M | 76 | 4,000 | 3,500 |

| 1981 | $16M | $1M | 120 | 5,100 | 3-4,000 |

| 1982 | $20.8M | $1.8M | 180 | 7,000 | 4,000+ |

| 1983 | $26.7M | -$69k | 400 | 8,000 | 3-4,000 |

| 1984 | $29.6M | -$750k | 167 | 8,600 | ?1,600+ |

| 1985 | $24M | -$3.8M | 96 | 6,000 | ?1,200+ |

1980 is clearly the year that everything went right. After years of doubling revenues, in 1980 revenues quadrupled, and meanwhile TSR’s Gen Con surpassed the wargame-focused Origins for the first time ever. In retrospective we know it’s all about what Peterson calls the “Treasure in the Steam Tunnels”: the national uproar over the disappearance of James Dallas Egbert III put D&D into the limelight and catapulted it toward national success.

1981 is usually referenced as the roleplaying industry’s high point in the ’80s, as seen by the sales of games like D&D and Traveller alike. But the thing is, sales didn’t decrease afterward: growth did. From 1981 to 1983, Peterson’s numbers show that TSR’s staffing increased by more than three times while revenues didn’t even double. The result? Profits became losses. A crash was clearly coming.

The last interesting thing about Peterson’s numbers is how bad things were still in 1985, with losses now grown to one-sixth of revenues, even as staffing had been quartered from its height. It’s particularly interesting because it’s usually marked as the year that Gygax saved TSR with products like Oriental Adventures (1985) and Unearthed Arcana (1985); although that certainly might be part of the answer, it’s clearly not the whole story.

What We Learn about the Hagiography of Gary Gygax

One of the greatest problems with the oral tradition of TSR has long been that it was largely controlled by Gary Gygax, both in his decade at TSR and in the time after he left. That long resulted in D&D co-creator Dave Arneson’s work on the game being minimized, something that was only somewhat corrected beginning in the ’00s, when Arneson returned to the hobby and its conventions.

It’s also resulted in histories that often present Gary Gygax as the hero who was betrayed by villains such as the Blume brothers and (especially) Lorraine Williams. Peterson doesn’t obviously set out to either push back on that hagiography or to rehabilitate Williams and the Blumes, but he does definitely tell a story based on as much fact as he was able to unearth, whether it agrees with Gygax’s narrative or not.

This includes:

- Discussions of how Gygax began to cut Arneson out of D&D’s history as early as 1977 (pp. 112-113).

- Reminders of Gygax’s claims that AD&D (1977-1979) was a different game from D&D (pp. 156-157), an assertion intended to also cut Arneson off from AD&D’s financial rewards.

- Pushback against 1980 statements from Gygax that he’d purposefully left full-time work to begin a game-design career (pg. 188).

- Revelations about how TSR began purposefully bowdlerizing their releases as early as 1982, with the full support of Gygax (pg. 234).

- Extensive descriptions of Gygax’s unproductive warfare with GAMA and Origins (pp. 238-239, etc).

- Discussions of how involved Gygax was in finding investors for the flailing TSR (pg. 289), contradicting his repeated narrative that he went running back to save TSR when he learned of its problems.

Obviously, we all remember our stories differently; obviously, we often paint ourselves as the heroes in our narrative. The above listing isn’t meant to be an attack on Gary Gygax. But it does suggest why it’s so important to go back to source material created at the time, rather than to depend on latter-day interviews (whenever possible, that is); that’s what Peterson has traditionally done, and why he’s able to offer new perspectives even on “well-known” events such as the first ten years of TSR.

What We Learn about the Warfare of Dave Arneson

Game Wizards also paints an interesting picture of Dave Arneson, who was originally depicted as a non-entity in the creation of D&D and later as a victim. Peterson organizes his book as a game in part because there were a lot of moves and counter-moves between Gygax and Arneson — even if the outcome was inevitable because the first had a company at their back and the rights to D&D and the other had only what he could extract from his foundational license.

But I found it interesting how much Peterson reveals Arneson as an active fighter against TSR: how nasty things got during his 1976 departure from TSR (pp. 92-100); how Arneson tried to undercut TSR through work with Heritage Models and Judges Guild (pp. 103-113); and how Arneson was himself trying to minimize the role of Gygax and even Chainmail (1971) in the creation of D&D (pp. 113-114, 145).

The anecdote that perhaps reveals the greatest height of warfare between Arneson and TSR is set at Origins IV (1978). D&D received a few awards, which TSR dutifully claimed, but when the award for “All Time Best Roleplaying Rules” was announced, Arneson raced to the podium himself to grab the plaque! No one raised a fuss at the time, but the con later asked Arneson to return the plaque and he refused (pp. 135-136). His argument was that individuals should be recognized, not publishing companies — an argument that today is still felt strongly by many designers, as publishers continue to remain in the driver’s seat for the entire roleplaying field, other than insmaller press categories such as indie and OSR publishers.

Conclusion

Game Wizards is unsurprisingly a very insightful book about the early roleplaying field. It presents the big-picture of TSR’s successes and failures from 1974-1985, but also offers deeply personal characterizations of important figures such as Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson. The book somewhat more approachable than Peterson’s original Playing at the World, without losing any of its academic sourcing.

Game Wizards is also just the first of two books on the history of TSR released in the last few years, with the next being Benjamin Riggs’ Slaying the Dragon (2022), which conveniently puts its focus on the latter half of TSR’s history: what happened after Gary Gygax’s 1985 departure!

This article was originally published as Advanced Designers & Dragons #72 on RPGnet. It followed the publication of the four-volume Designers & Dragons (2014) from Evil Hat, and was meant to complement those books.

[…] best year with D&D was 1982, the year before I began playing! Jon Peterson’s numbers tell us it was the last year both revenue ($20.8M) and profit ($1.8M) grew. After that, TSR was […]