This A to Z of roleplaying games was originally written for the A to Z blogging challenge in April and debuted on the Designers & Dragons Facebook group. It’s alphabet-focused description of 26 RPGs that were inspirational, influential, or innovative. When possible, games were also selected that might be a little less-known than the top releases for each letter.

This article can also be downloaded as a PDF file, laid out in two-page spreads.

A is For Ars Magica

The most influential RPG in the industry that you’ve likely never heard of (let alone played) is Ars Magica (1987), the first publication out of Lion Rampant, designed by Mark Rein*Hagen and Jonathan Tweet.

The game is a pseudo-historical fantasy where all the folktales and legends are true. And, it’s about wizards. Stepping away from the tropes of D&D was pretty innovative, as was focusing a game on a specific “class” of character. This was in an era where the big games like D&D (1974), Tunnels & Trolls (1974), Chivalry & Sorcery (1978), and Rolemaster (1982) were largely iterating those tropes using Variant D&D mechanics — and even the more innovative RuneQuest (1978) was often delving into dungeons like Balastar’s Bararcks and The Big Rubble. Nonetheless, there was one major predecessor for this style of play, Greg Stafford’s King Arthur Pendragon (1985), which nailed the idea of legendary history and of roleplaying that emulated a single type of character.

But Ars Magica was more than that. It also excelled in breaking down the tropes that had previously defined our hobby’s group dynamics, with its “troupe roleplaying”. There was no longer a promise that characters would be balanced: some players took on the roles of powerful magi and others servile grogs. There was no longer the need for a single gamemaster: multiple players came together to shape a narrative. Even the flow of play was disturbed, with storylines flowing and ebbing around “seasons” of time, so that the magicians could study — as magicians do. (Admittedly, this last one had precursors in King Arthur Pendragon as well!)

But Ars Magica wasn’t influential just for the ideas it brought into the gaming field, but also for the designers: Rein-Hagen and Tweet.

Mark Rein-Hagen went on to design Vampire: The Masquerade (1991) for White Wolf. Though in retrospective, the original World of Darkness shared some play with the superhero games of the previous decade, it was still one of the most innovative RPGs published to that date, both through its reinvention of styles of play (by putting interpersonal interactions through the roof) and through its expansion of the demographics of the hobby.

Jonathan Tweet went on to design Over the Edge (1992), the first game to not just push back against the growing complexity of RPGs in the late ’80s and early ’90s, but in fact to offer a much more open and freeform methodology. In many ways, it was the foundation of the indie movement of the ’00s (though once again, one can date some ideas to Pendragon and other emulative games, beginning with the fact that “system matters”). Then Jonathan Tweet went on to lead the design of D&D 3e (2000), which thanks to the OGL was the most important game of the ’00s.

Ars Magica, now in its fifth edition, remains in print today thanks to the long-term support of Atlas Games, though new supplemental publication closed out back in 2016. Not bad for a small-press RPG produced on a Macintosh computer with bleeding edge DTP way back in 1987.

B is for Blue Rose

When Wizards of the Coast released D&D 3e (2000) under the OGL, it was not a gift of charity, but instead unadulterated self interest. They wanted other publishers to stop working on their own game systems and to instead support Dungeons & Dragons, to ensure that it remained the leading game system and that other companies would produce the supplements that weren’t cost-effective for Wizards, adventures prime among them.

Those other publishers promptly used the SRD to create totally new games. This was a huge surprise for Wizards as it wasn’t at all their intent. But the creation of new games systems was also one of the greatest joy of the d20 Boom, because it meant that styles of gameplay that hadn’t previously been seen in the gaming mainstream could suddenly gain the attention previously only granted to the hobby’s premiere game system.

Enter Green Ronin, previously the creators of Mutants & Masterminds (2002). As a superhero-based d20 system, Mutants & Masterminds was pretty cool, but there were other superhero RPGs going back to Superhero ’44 (1977) and there was even Guardians of Order’s Silver Age Sentinels (2002) in the same superhero-d20 space. But Mutants & Masterminds gave Steve Kenson the experience to co-design and develop Blue Rose (2005), alongside Jeremy Crawford, Dawn Elliot, and John Snead; and it gave Green Ronin the experience to produce it and the reputation to sell it.

Blue Rose, which used a stripped-down version of the d20 system via some of the advancements in Mutants & Masterminds, advertised itself as “The Roleplaying Game of Romantic Fantasy”. Now, that doesn’t actually mean FRPGs with romance thrown in. Romantic Fantasy is instead a very personal, character-based subgenre of fantasy, where protagonists tend to be loners facing emotional struggles. They tend to live in very human-focused worlds, which likely increases the focus on people and their internal lives. Finally, romantic fantasy also tends to be much more progressive in regard to gender roles and sexual orientation.

That last bit in particular is what made Blue Rose extremely special back in 2005. It was a bastion of diversity, openness, and acceptance, back in a time period when openness itself was not widely accepted in society. It appeared before the indie design scene did more than touch upon these ideas, and it appeared in the mainstream thanks to its d20 roots. It was groundbreaking in a way that few RPGs can be: socially, societally, and culturally groundbreaking.

Though Green Ronin has moved away from their d20 roots, Blue Rose has reappeared as Blue Rose: The AGE Roleplaying Game of Romantic Fantasy (2017), using their newest house system.

C is for Castle Falkenstein

The story of Castle Falkenstein (1994) is not just about Mike Pondsmith’s innovative game design, but also his impressive ability to foresee the genre trends that would soon become popular. For years, he’d been beating the rest of the industry to the next big thing, resulting in games such as Mekton (1984), Teenagers from Outer Space (1987), and most notably Cyberpunk (1988), each of which brought a new genre of play to the industry. Now Castle Falkenstein highlighted the steampunk genre that was being popularized by The Difference Engine (1990). Granted, Space: 1889 (1988) had tread some of the same ground, but it was Castle Falkenstein that would see more popularity, while Space: 1889 had already come and gone.

That may be in part due to the innovative way that Castle Falkenstein carried its newly introduced genre into the rulebook itself. That was partly done through a fun bit of fiction at the start, an idea inherited from Vampire: The Masquerade (1991), but the theming went far beyond that. Players had diaries instead of character sheets, and, because only riff-raff would use dice, cards were used as the game’s randomizer.

The last bit was Castle Falkenstein’s third major innovation, after its genre and its integrated theming. Though cards had been used in specialized decks and to give players some agency previously, Castle Falkenstein, was the first RPG to use them as its core randomizer — and more than that, as a resource, because certain numbers of certain suits of cards were required to complete certain tasks. This idea would become a major area of roleplaying development in the decades that followed.

All told, it’s tempting to call Castle Falkenstein an early indie, but perhaps it’d be more accurate to say it had indie theming and design, but in a mainstream package.

Castle Falkenstein wasn’t a major success for R. Talsorian. It was down to just a single supplement of support in each of 1996 and 1997, before R. Talsorian powered down in 1998. Nonetheless, it returned as GURPS Castle Falkenstein (2002) a few years later and was supported with a new series of PDFs when R. Talsorian rebooted in the ’10s.

It’d also be accurate to say that Castle Falkenstein showed everything that was right about R. Talsorian and what made them a great roleplaying publisher: even today it remains a thematic, innovative, and future-looking game.

D is for Delta Green: The Role-Playing Game

Chaosium’s Call of Cthulhu (1981) really got the horror genre going for roleplaying games, and it may well be the reason that H.P. Lovecraft’s fiction survived into the twenty-first century as a notable literary force. But, by the ’90s it was comparatively staid, especially when compared to the personal horror of Vampire: The Masquerade (1991) and the more modern imaginings of Kult (1993) and The Whispering Vault (1994). Even Keith Herber’s excellent Lovecraft Country series was treading classic ground, which is to say the 1920s.

Enter Pagan Publishing. From the debut of The Unspeakable Oath (1991), it was obvious that they were offering a much more modern take on the Cthulhu Mythos. The Chambersian visions of John Tynes, the horrific artwork of Blair Reynolds, and the imaginings of many others brought a new freshness to the Cthulhu Mythos, resulting in some of the best Cthulhu supplements of that decade.

But five years on they produced something even more notable: Delta Green (1996). The whole idea of Modern-day Cthulhu scenarios can probably be attributed to Marcus Rowland and the “Cthulhu Now!” articles that he originally wrote for White Dwarf (1983) and later revisited in Trail of the Loathsome Slime (1985), which in turn led to Cthulhu Now (1987). But those various adventures and supplements tended to transport the idea of the Mythos to the modern day without truly making it their own.

Delta Green was something else. It didn’t just drop the Mythos into a world of computers, airplanes, and corporations; it instead reimagined the myths, folklore, and legends of the modern day through the lens of the Mythos. Greys, men-in-black, government conspiracies and more all became part of the story that Lovecraft had discovered in the 1920s, creating a new style of horror for a world that was becoming complacent in the shadow of Glasnost. It was the horror of the secrets and cracks that lie almost invisible beneath the surface of our seemingly safe world. The result was very successful and helped Pagan Publishing to at least remain par with their licensor across the decade (and sometimes do more).

But, there was always a problem with Pagan’s success: they didn’t own the Call of Cthulhu game, and so they were always beholden to Chaosium. They had limits to how many books they could produce (not that they were that likely to produce more: Pagan would always keep working at a project until it was perfect), they couldn’t control changes that might be made to the system, and they ultimately couldn’t see the greater success and benefits that accrue to a publisher able to produce not just supplements, but evergreen core rules.

Fast forward two decades. Pagan is gone, but that is not dead yadda yadda yadda, and thus Arc Dream Publishing has risen up in their place. In 2015, Arc Dream Kickstarted Delta Green: The RPG, which was published as an Agent’s Handbook (2016) and then a Handler’s Guide (2018). It’s ultimately based on similar mechanics to Call of Cthulhu, courtesy of the RuneQuest OGL license offered by Mongoose, but also reimagined with rules for bonds, extraordinary results, and more, making it a somewhat more modern offering (though Call of Cthulhu of course modernized itself a bit in a 7th edition around the same time).

Delta Green: The RPG is what Delta Green had always needed to find a level of professional success that matched its critical success. Since the Kickstarter, there’s been a renaissance of Delta Green material … but not necessarily the sort of material that you would have seen for the old Delta Green sourcebook. That’s because Arc Dream has proven that it’s continuing down same path that helped bring Pagan success in the first place: they’re no more repeating the tropes of ’90s Delta Green than that book repeated the tropes of ’20s Lovecraft. Instead, Delta Green: The RPG reimagined its world. It’s no longer the world after Glasnost, but instead the world after 9/11. Times are harsher and the corruptive forces of the Mythos are no longer quite as secretive. Instead they’re a “thousand points of horror” ready to bring down civilization.

It’s a new Delta Green for a new era, something that many settings and many games could perhaps learn from.

E is for the Esoterrorists

So much comes back to Chaosium’s Call of Cthulhu (1981). It was the game that brought horror roleplaying into the mass-market and the game that ensured H.P. Lovecraft’s continued relevance in the 21st century. It was the release that proved that Chaosium’s BRP system, which debuted in RuneQuest (1978), had legs. But it was also the game that brought investigative gameplay to the roleplaying hobby.

That was just a mimicking of the styles of Lovecraft’s fiction. There, protagonists learned of weird happenings, investigated said weird happenings, and then went crazy. Not the best result, granted, but a clear trope of the fiction. By bringing that trope to roleplaying, Call of Cthulhu invented a new way to roleplay, different from the dungeon-delving of D&D (1974), the mercantile or mercenary activity of Traveller (1977), or the supervillain fighting of Champions (1981).

Call of Cthulhu did a magnificent job of incorporating investigation into its adventures by producing some of the earliest player handouts in the hobby and then doubling down on them as graphic design capabilities improved. Handwritten letters, adulterated photographs, and newspaper entries all offered different ways for players to accumulate information. That was supplemented, of course, by plenty of roleplaying with NPCs and discovering other clues through the game.

Call of Cthulhu wasn’t the only game to go this way. Victory Games’ James Bond 007 (1983) was another standout, the quality of their handouts pushed even further than Chaosium’s because Avalon Hill was fundamentally a printer, and thus they had the ability to drop all kinds of little gimmicks into their boxed sets.

The problem with classic investigative RPGs was always the possibility for accidental failure. Oh, whole articles could be written on whether failure is or isn’t appropriate in roleplaying game, and the question marks a big division between old-school and new-school play. But failure is particularly problematic during an investigation because it can derail the entire story. You miss a single clue, which could happen with a failed skill roll, and it’s all over. There’s a huge anticlimax and everyone goes home.

Enter Robin Laws and The Esoterrorists. In The Esoterrorists, Laws debuted a new game system called GUMSHOE. It was designed at the request of Pelgrane Publishing founder Simon Rogers, who wanted a game that streamlined mysteries, but Laws decided to zero in on the problem of missing clues. Thus in GUMSHOE, you never can: clue discovery is automatic if you have the right skills. Granted, investigations can still fail if players can’t figure out how to put the pieces together, but that makes the question one of player agency, not randomness.

The setting for The Esoterrorists was a new take on the cosmic horror that also underlies the Lovecraftian mythos. Esoterrorists (cultists) are trying to break down the walls of reality, letting in monsters of the subconscious who dwell in the Outer Dark. There were also plenty of conspiracies in this secret world, repeating the tropes of more modern RPGs, from Over the Edge (1992) to Delta Green (1996). (With all that said, the first edition of The Esoterrorists mainly left things up to the GM, as the setting material was pretty sparse.) This all highlighted The Esoterrorists’ niche, which was as an alternative to Call of Cthulhu. It was a niche people were interested in. The world of The Esoterrorists, though a bit thin and experimental, generated a strong line of several books and eventually a more fully featured second edition (2013).

However the real brilliance of The Esoterrorists lay in its game system. It had legs! The idea of never failing at discovering a clue was wildly popular as was the fairly simple game system. Both allowed players to get to the good stuff of investigation, which is putting the puzzle pieces together, not rolling dice and hoping not to go home! As a result, The Esoterrorists has spun off a large number of alternative games. A more traditional Lovecraftian game appeared in Trail of Cthulhu (2008), which was probably what helped GUMSHOE to really break out. But the superheroes of Mutant City Blues (2009) and the science-fiction of Ashen Stars (2011) were among the releases that showed what all GUMSHOE could do. In more recent years, Pelgrane has gone further afield with prestige releases such as The Dracula Dossier campaign (2015) for the Night’s Black Agents game and The Yellow King RPG (2018) as well as crossovers such as The Fall of Delta Green (2018).

GUMSHOE has been the engine for some of the most innovative and thoughtful mass-market horror games of recent years, and that all started with a small, experimental little RPG called The Esoterrorists.

F is for Fiasco

The indie design scene was foreshadowed as far back as King Arthur Pendragon (1984) and Ars Magica (1987), incubated in Hogshead’s New Style releases beginning with The Extraordinary Adventures of Baron Munchausen (1998), and properly birthed through Sorcerer (1996) and the community that Ron Edwards created in its wake at the Forge.

In the ’00s, this indie roleplaying movement introduced any number of innovations to the form. Its designers were more willing to invent new mechanics. They tended to give players more agency, and sometimes did away with GMs entirely, turning roleplaying into a more fully collaborative form. They also tended to focus on more realistic (or sometimes surrealistic) genres rather than the fantasy and science-fiction that’s at the heart of so many roleplaying games. In many ways the indie games were a reinvention of roleplaying.

If the indie movement had one flaw in the ’00s, it was approachability. The indie community tended to be small, and even when their books were released out into distribution, their reach was limited. A few games such as InSpectres (2002) and Primetime Adventures (2004) got some attention, but they didn’t hit the full mass market. Nothing did. Until Jason Morningstar’s Fiasco (2009).

Fiasco is a heist-gone-wrong adventure game. Each player creates a character and then builds connections with each other character — connections that are made concrete with a specific detail. Individual playsets from “Boom Town” to “Suburbia” give the players more story elements to play with. Finally, a “Tilt” shakes things up halfway through the game and offers new plot seeds going into the second half of the story. Tied into this cornucopia of plot elements are several indie mechanics, such as GM-less play where different players always establish and resolve scenes, spreading out the authority in a way that was unknown in classic games before the indie revolution.

Fiasco is a wonder of simplicity and compactness. It’s tight and carefully constrained, making it a perfect one-off or con game. It’s also a wonder of approachability with its familiar genre and its ease of connections and twists, ensuring that play never stalls out and there’s always something else to do. It’s a wonder of theming, creating evocative and immersive stories. Finally, it’s a wonder of modularity, with additional playsets supporting gaming pretty much anywhere and anywhen.

If you only ever try a single indie game, it should probably be Fiasco.

Ten years on, Fiasco doubled-down on its accessibility when Jason Morningstar produced Fiasco in a Box (2019) which put the entirety of the game onto cards. The original remains available as Fiasco Classic.

G is for GURPS

You could certainly argue over who debuted the idea of a universal roleplaying system. Palladium Books at one time claimed they did, on the strength of their publication of The Mechanoid Invasion (1981) which used the same house system as Palladium Fantasy (1983), published a few years later. The Hero System similarly developed from Champions (1981) to Espionage (1983). Designers & Dragons prefers the BRP system, which developed from RuneQuest (1978) to the BRP booklet (1980) to Worlds of Wonder (1982), the first RPG to use the same system for multiple genres within a single product.

But, to a certain extent that’s all academic. Steve Jackson’s GURPS (1986) must be recognized as both the first game to fully embrace the idea of a universal roleplaying system and the game that popularized the idea so much that it became almost a de facto standard for design in the ’90s.

Ironically, GURPS started its life in fantasy, which is perhaps not a surprise given its evolution from Jackson’s then-lost original designs, Melee (1977), Wizard (1977), and The Fantasy Trip (1980). Similarly, GURPS kicked off with Man to Man (1985) fantasy combat and Orcslayer (1985). But with the release of both GURPS Autoduel (1986) and GURPS Fantasy (1986) following the publication of the GURPS first edition, Steve Jackson proved that GURPS could successfully model widely disparate settings.

The concept of universal rule systems suffered somewhat of a setback in the ’00s. On the one hand you had the indie community preaching that “System Matters”, and that games could be better if their rules were closely linked to the own settings. On the other hand, you had D&D’s release under the OGL turning much of the industry toward fantasy while simultaneously subverting universal system by also seducing publishers into using d20 mechanics for more far-flung science-fiction or espionage games. It’s only been more recently, with the rise and growth of Savage Worlds (2004) that true universal systems have become cool again.

But GURPS showed why they were cool all along, and it was primarily about the supplements.

Through Jackson’s creation of a game system that had very wide applicability thanks to its careful simulationist design, Steve Jackson Games was able to produce what may be the most impressive supplement line in all of gaming. Across hundreds of supplements, Jackson brought more beloved settings to gaming than any other publisher, from licensed books such as GURPS Conan (1989), GURPS Humanx (1987), GURPS The Prisoner (1989), and GURPS Wild Cards (1989) to classic settings such as GURPS Scarlet Pimpernel (1991). They translated other games, such as GURPS Blue Planet (2003), GURPS Castle Falkenstein (2000), GURPS Vampire: The Masquerade (1994), and the longrunning GURPS Traveller line (1998) while also creating settings of his own such as GURPS Fantasy: The Magic World of Yrth (1990), GURPS Space: Terradyne (1992), and Transhuman Space (2002). Perhaps most impressively, they created not just numerous genre books such as GURPS Horror (1987), the much-storied GURPS Cyberpunk (1990), and GURPS Supers (1991), but also a library of real-world setting books so huge that it would make any amateur historian swoon with delight, such as GURPS Aztecs (1993), GURPS Ice Age (1989), GURPS Japan (1988), and GURPS Middle Ages I (1992).

You can’t look at a list of GURPS publications without being constantly amazed by the scope of the offerings — and wanting to read many of them!

GURPS has been at a low-ebb for years due to the comparative success of the Munchkin card game (2001), but over 100 books in its classic library are now available as print-on-demand, while new support continues with Kickstarter projects such as as the Girl Genius RPG (2021) and new GURPS-focused Pyramid magazines (2022). And thus the library grows ever larger.

H is for HōL

HōL: Human Occupied Landfill (1994) will likely end up being the RPG in this A to Z listing that’s been the least played. That’s because playing it really wasn’t the point. And, it wasn’t necessarily an influential game either. But it was groundbreaking — and beyond that a real milepost for the industry’s increasing maturity.

HōL has been produced by Dirt Merchant Games (1994), White Wolf (1995), and The CaBil (2002). Obviously the middle edition is where the game got its most attention, though that was built on extensive critical acclaim and interest in the Dirt Merchant original. The premise is simple enough: HōL is set in a SF universe where players are trapped on a garbage-dump/penal-colony world and must survive. The mechanics are … well, minimalistic. There isn’t even a character-creation system, just a set of pregenerated PCs, ala the original design of The Adventures of Indiana Jones (1984).

However, rather than really being a game, HōL is instead a satire. The entire book is handwritten. It mocks other games. It mocks gamers. It mocks itself. Its skills are silly names. When a character creation system did finally come along in Buttery Wholesomeness (1995), the only HōL supplement, it was a labyrinthine series of charts that parodied Traveller.

HōL was thus the first example of RPG-as-art-object, a baton that’s been picked up by another game with weird diacritics, Mörg Borg (2020), and other artpunk RPGs. It was the first example of an RPG that was intended to be read at least as much as it was intended to be played. It wasn’t the earliest satire in the industry: there had been wonderful satires before, like Paranoia (1984), and horrible satires, like WG7: Castle Greyhawk (1987). But it was the first RPG to so totally fill itself with satire — exactly because it didn’t have to be a functional game.

In many ways HōL demonstrated the maturity of the roleplaying market. By 1994, there were a large enough population immersed in a wide expanding roleplaying hobby, and a widely expanding roleplaying culture, that there were sufficient people willing to stop and read a bizarre mockery of the hobby and able to understand its many in-jokes.

In Interactive Fantasy magazine, James Wallis compared HōL to Bored of the Rings and called it the “funniest role-playing-related product” that he’d ever read. That, along with its ante-artpunk stylings is what made HōL innovative at the time. Today, it still remains interesting as a time capsule into a different era.

I is for Inspectres

Though Fiasco (2009) is the game that really broke open the indie category and brought it to the attention of a somewhat wider audience, there were a couple of predecessors that got some mass-market acclaim; one of them was Jared Sorensen’s Inspectres (2002).

Inspectres is essentially “Ghostbusters: The Reality TV Show: The Roleplaying Game”. Now the first part of that equation had already been done well by the Chaosium crew in the classic Ghostbusters (1986) RPG. It’s the latter parts that really caused Inspectres to hit it out of the park: a roleplaying game that took the shape of a reality TV show.

When Sorenson was developing Inspectres, the indie community was still in a very formative stage. Thus his idea of player/character divide was quite new for the hobby. It posited that while players take on the roles of characters, they simultaneously can metagame outside of their character role. Though the idea seems obvious enough, it isn’t supported by classic RPG mechanics. It’s pretty hard in D&D, or really most traditional RPGs, to be acting orthogonal to the goals and even interests of your character: there’s just no way to do so as long as your only way to affect the gameworld is through the actions of your character.

Inspectres introduced that orthogonal mechanism via confessionals: a variety of interviews that characters give “to the camera” throughout the game. There are interviews that get each game going, and then there are confessionals throughout the game that report how things are unfolding and what a character thinks about them.

The thing is, those confessionals don’t have to solely be based on events that have already occurred. They can also introduce new story elements that hadn’t been obvious in the game so far, or even foreshadow the future of what is still to occur. As a result, each player gets to shape the game beyond just their character’s actions within the game. They can introduce their own challenges, create their own spotlights, or just get the ball rolling on plots that they’re interested in playing through. That’s the player/character divide right there: interacting with the game in both the role of player _and_ character. And it’s all done via a well-constrained mechanic that gives players this limited authority without dumping them into the narrative deep end.

The rest of Inspectres is a clean, evocative, and fun game. There are even some other ways for players to minorly control the story, such as when they succeed at a skill. But it was the confessionals that really innovated the form, both through their specific mechanics and through the larger questions those mechanics asked about what it meant to play an RPG.

The tongue-in-cheek world creation of Inspectres was also innovative enough that it spun off a small-press Inspectres movie (2013). It’s a pretty rare game that can say that!

J is for James Bond 007

Obviously, Top Secret (1980) got the espionage roleplaying category going, with Espionage (1983) bringing the genre to HERO just a few years later. But that same year James Bond 007 (1983) also appeared, and it was the espionage RPG to really knock the ball out of the park, thanks both to its great design and production. (Grognardia suggests that it was likely the best-selling espionage RPG of all time.)

Much of that is thanks to James Bond 007‘s excellent pedigree. Its story begins with TSR’s amoral financial manipulations of SPI, which allowed them to capture and kill the classic wargame producer. Most of SPI’s designers wanted little to do with their company’s killer and so within days of TSR’s hostile takeover of SPI, eight of them jumped ship to Avalon Hill, among them John Butterfield, Mark Herman, Gerry Klug, and Eric Smith. There they formed a new subsidiary: Victory Games.

Victory produced over 50 games, including the innovative paragraph-based wargame Ambush! (1983). One of those games was an RPG: James Bond 007. (It would also be well-supported with supplements.)

So what made James Bond 007 great? That answer comes in at least four parts.

First, you had great game design from Gerry Klug. The game was foundationally simulationistic, which is somewhat less in vogue today, but it was a simulation that really expanded on the designs of the time, including point-based characters, a unified task system with easily adjustable difficulty levels, and a Quality Results Table that allowed variable levels of success. Obviously, point-based characters dated back to The Fantasy Trip (1980) and Champions (1981), but the idea wasn’t yet widespread in the industry, while James Bond 007‘s task and results system was quite novel.

There were also a few other mechanical innovations, apart from the game’s core simulation. The most important was Hero Points a renewable resource that allowed players to adjust their level of success, a stunning amount of player agency for the era. Clearly, it was inspired by Top Secret‘s Fame and Fortune points, but those were focused on survival and beginning characters respectively, while Hero Points were a much more ingrained part of the James Bond 007 system. Another was the game’s intriguing chase system, which actually allowed players to _bid_ levels of difficulty to achieve success. Shades of indie design 15 or more years down the road!

The second thing that made James Bond 007 great was the license for James Bond. Especially back in the ’80s, Bond was the public’s prime icon for espionage. Sure, you had The Avengers or The Man from UNCLE TV shows or the excellent writings of John Le Carré. But not only was James Bond better known than any of them, but his big-screen exploits had become the archetype for spies. A James Bond RPG could be no less.

Third, you had excellent adventure production from Avalon Hill (which is to say Victory Games), with adventures based on the movies (more or less) each appearing in boxed sets. Perhaps more than any other category of roleplaying, adventures can make or break mystery and espionage RPG sessions, and Avalon Hill didn’t stint. Because Avalon Hill was a printer, those boxes also tended to include printed clues of various sorts that added to the verisimilitude (and fun!) of the play.

Beyond all of that, James Bond 007 excelled as a licensed product, really showing the way for games of this sort when extant publications like Stormbringer (1981) and forthcoming products like MERP (1984) and The Adventures of Indiana Jones (1984) didn’t always make the best use of their source material. It do so by turning the simulation into emulation. James Bond 007 feels Bondesque top to bottom, back in an era when no one had ever said “System Matters”. That was aided and abetted by those adventures, which really nailed the feeling of action-packed over-the-top espionage. But throughout all of that, the designers were also thinking carefully about how to cleave close to their license without hewing so near that players could be spoiled for the events of some of the movie-adventures; thus the movies were sometimes just jumping off points for the similarly named adventures, and when they were more tightly connected, major scenes or events were sometimes changed to keep players on their toes.

Maybe some impressions of James Bond 007 are rose-colored today, but it was certainly innovative and inspirational in its time: a masterwork of 1983 game design.

Unfortunately, James Bond 007 would ultimately be let down by both its publisher and its license. It went out of print in 1987, by which time Avalon Hill was already floundering in the roleplaying business. In later years, the creators of Avalon Hill-published games such as RuneQuest (1978) and Tales from the Floating Vagabond (1991) had to jump through big hoops to recover their games as Avalon Hill was sold off to Hasbro. James Bond 007 likely still lays there in Hasbro’s vaults, and is simultaneously unpublishable because of its license.

With that said, the game system has been revived as the DoubleZero retrocolone (2008), which has recently become a prolific line, and as Classified (2013).

K is for King Arthur Pendragon

Four emulative icons of the mid ’80s led the way for storytelling in roleplaying games: James Bond 007 (1983), Paranoia (1984), Ghostbusters (1986), and perhaps most notably Greg Stafford’s King Arthur Pendragon (1985), the Arthurian Roleplaying Game.

Though James Bond 007 might have demonstrated how roleplaying games could emulate specific styles of play, King Arthur Pendragon was the game that nailed down the style and offered it up to the indie design community to come. It’s a game about knights, and that’s it. There are no thieves, no clerics, no magic-users (except briefly in fourth edition). There are knights and their activities. Tournaments, jousting, feasting, and warfare are all placed in the rules specifically to encourage and to support play based on Le Morte d’Arthur. It’s a game of knights about knights and for knights.

If there are other innovations in King Arthur Pendragon, and there are, they all originate from this same heart of emulation.

Personality traits and passions are usually noted as another of the novel aspects of Pendragon. These are paired traits like Chaste/Lustful, Valorous/Cowardly, and Merciful/Cruel and more general concepts such as Love (Family) that can guide players in their roleplaying. However, they can also take over characters if they are allowed to grow too large, just like the wild madnesses that knights sometimes experienced in Le Morte.

The unhurried and measured take of King Arthur Pendragon is yet another nod toward its source material. Adventures often intrude upon players at a feast or some other mundane event, leading them into the wilds of adventure, but afterward characters retire away until the next year’s story. It makes the everyday of the life of the knights that much more real, while simultaneously turning adventures into phantasmagoric and dreamlike interludes.

This staccato pace had two additional effects.

The first was the introduction of winter phases. For the first time ever, roleplaying wasn’t just about what happened in adventures, but also what happened in-between, allowing players to engage in roleplaying interludes amidst the large stories and to build up their resources in a way that any powergamer would love. Ars Magica (1987) and The One Ring (2011) have advanced similar ideas, but as was so often the case, Greg Stafford got there first.

The second was the introduction of generational roleplaying. Just as the central story of the Matter of Britain is about Uther, Arthur, and Modred, so does King Arthur Pendragon follow the paths of a character, their children and, and their childrens’ children. Rules carefully allow for continued advancement across the generations, ensuring that players would want to engage in this roleplaying that was unlike any other.

However, the greatest success of King Arthur Pendragon may not have been in its wonderfully thematic rules, but instead in what could be the roleplaying industry’s most notable campaign book ever: The Great Pendragon Campaign (2006). Building on the generational, staccato roleplaying of King Arthur Pendragon, The Great Pendragon Campaign offers a storyline spanning 80 years, from 485-566. There is nothing else in the roleplaying field that has that scope of time and imagination. It’s literally the campaign that King Arthur Pendragon was create to enable, even if it took over twenty years to get there.

After a considerable time away from home, King Arthur Pendragon has happily returned to original publisher Chaosium in recent years. A Quick Start for the impending sixth edition called The Adventure of the Sword Tournament (2022) premiered last year, with a Starter Set (2023?) waiting in the wings.

L is for Labyrinth Lord

When Wizards of the Coast made their self-serving decision to release the d20 mechanics under an OGL, they opened up a Pandora’s Box of unexpected consequences. They thought they were mainly allowing other publishers to produce adventures, but they cleared the path for competitive supplements like the Creature Collection (2000) and competitive RPGs like Pathfinder (2009). They allowed the creation of fantasy variants such as Blue Rose (2005) and more farflung d20 games such as the superheroic Mutants & Masterminds (2002) and the science-fiction T20 (2002). Perhaps most surprisingly, they allowed for the resurrection of all the old versions of D&D as part of the OSR.

This was back in the era before PDFs (let alone PODs!) were available for old games. The classic AD&D game (1977-2000) had just been replaced with D&D 3e (2000), and for the moment it seemed that the hobby’s most nostalgic games, the versions of D&D that had brought many into the hobby, were gone forever. Though supplements still filled many a gamer’s shelves, and though there was still interest in publishing more, there would no longer be rule books to allow those game systems to continue and prosper.

Enter Matt Finch, who created the theory of a legal retroclone: he posited that the copyrightable material encoded in the D&D 3e SRD could be combined with uncopyrightable game mechanics matching older game systems to resurrect those legendary games in a legal manner. The result of that theory was OSRIC (2006), a retroclone of AD&D, whose initial release demonstrated the classic possibilities of the OGL.

But OSRIC, and its contemporary Basic Fantasy Role-Playing (2006), were focused on the online OSR community, had limited production through PDFs, PODs, and short print runs, and had various levels of non-commercial philosophy built into them. For the OSR to become not just a hobbyist innovation, but a commercial innovation, required something else, and that something else was Dan Proctor’s Labyrinth Lord (2007).

The first thing that makes Labyrinth Lord a standout was that Proctor imagined it from the start as a living line, not just a book. More importantly, he put it into game stores — initially through Key 20. As a result, OSR rulebooks became widely available for the first time ever, letting modern players know that they could play a variety of games, not just the ones being currently manufactured by the big producers. We often talk about the increased agency of RPG players in the 21st century: Labyrinth Lord, and the rest of the OSR, offered increased agency to RPG consumers instead.

Second, Labyrinth Lord retrocloned what may have been the most accessible and well-known version of D&D ever, the B/X rules. It was a game that had originally been taught in Tom Moldvay’s tight 64-page rulebook (1981). Its iconic green character sheet had been a wonder of simplicity, while its Erol Otus cover had been a touchstone for all gamers of a certain age. It was published at D&D’s early height, with the Basic D&D line tallying up more than a million sales during the two years when it was the core rules. (Again, Basic Fantasy got here first, but it had the strictest non-commercial requirements of all, which kept it from breaking out like Labyrinth Lord did.)

Third, Proctor doubled-down almost immediately with the publication of Mutant Future (2008), a Labyrinth Lord variant that (more or less) retrocloned the classic Gamma World game (1978, 1983). In doing so, Proctor (and Labyrinth Lord) helped to kick off the next era of OSR production, where creators began to redevelop classic game systems to create games in new genres, with new styles.

Through its innovations, made as part of the collaborative OSR community, Labyrinth Lord in turn led to the success of Swords & Wizardry (2008), where Matt Finch returned to combine his own legal lessons from OSRIC with the community and publication lessons from Labyrinth Lord to bring the OSR even greater mass-market success.

Labyrinth Lord has remained available through the years, and remains one of the three core publications that give the modern, commercial OSR its foundation. But Proctor turned to other projects in the ’10s before ultimately returning with the cleaned-up Advanced Labyrinth Lord (2019) and kids-focused Lordling (2019). Old-School Essentials (2017, 2019), yet another game that likely wouldn’t exist without Labyrinth Lord, picked up the B/X baton in that time.

But recent events demonstrate that the future of Labyrinth Lord remains just as innovative as it was back in 2007. Wizards of the Coast’s failed attempt to destroy the OGL in early 2023 led Proctor, who at the time was working on a second edition of his classic game, to start considering alternative designs for Labyrinth Lord. Realizing that the world was far different from 2007, when a book like Labyrinth Lord was necessary to allow the continued play of a classic game system, he began going further afield in his design, considering new classes such as brownies and cyclops, new methodologies for spell-casting, and a new feel for the game.

It’s the continuation of the very trend that Proctor began with Mutant Future, allowing him to create a new FRPG that suits his own interests, but is still based on a well-loved classic design.

It’ll still be Labyrinth Lord, just for a new era of play.

M is for Mutant Year Zero

Though roleplaying started in the United States, with Dungeons & Dragons (1974), and though D&D and many other English-language RPGs have been exported across the world, many non-English-speaking countries also have their own intriguing histories of roleplaying creation. Perhaps the greatest of those is the story of Swedish design.

It did begin with an import: Chaosium’s Basic Role-Playing (1980) and Magic World (1982), which Fredrik Malmberg’s Target Games translated into Swedish. Add on a brand-new adventure and you have the primordial Swedish RPG: Drakar och Demoner (1982). The game would transform into its own design over the years and also accrue a few companions at Target, the first of which was the post-apocalyptic RPG Mutant (1984).

For decades, Target went from strength to strength, largely defining tabletop roleplaying in Sweden, before Malmberg eventually spun his work off into a Hollywood-focused corporation that today owns the rights to not just several of Target’s former games, but also Robert E. Howard’s Conan.

Target’s retreat from the tabletop roleplaying field offered room for new entrants, and the greatest of those has been Fria Ligan, or The Free League. Fria Ligan’s first few years were spent publishing supplemental and original material for the Swedish market, but then they decided to enter the global market when they acquired a license for one of the country’s primordial games. They negotiated for Drakar och Demoner, but didn’t like the final terms, so they instead licensed Mutant from Malmberg.

Rather than sticking with Mutant’s original BRP system, designer Tomas Härenstam instead adopted an indie-influenced post-apocalyptic system that he’d been working on for years, called “Version Noll”. The end result was Mutant: År Noll (2014), or Mutant: Year Zero (2014).

Mutant: Year Zero is intriguing in part just because it’s a Swedish roleplaying game. It’s part and parcel of a few decades of parallel evolution of design sensibilities, which included a willingness to bring indie ideas into the mainstream, something that wasn’t yet a big focus in the English-language RPG world.

But, Mutant: Year Zero was a magnificent design beyond that. It’s what Härenstam calls a “neotrad” design. It has a traditional setting and playstyle, but it also incorporates indie mechanics, such as resource management and improved player agency. Thus, Mutant: Year Zero uses a simple dice pool where sixes are successes, but allows for rerolls where each reroll increases the odds of success and simultaneously the odds of trauma. (That’s indie-influenced player agency there.) This ties into a mutation system that creates a system of rising tension in the game, which climaxes at an adventure’s finale.

There’s a lot more to Mutant: Year Zero. The character generation is quick, based on fun archetypes that could have come out of Apocalypse World. The mutations are powerful and evocative. Combat is potentially deadly, creating a real sense of danger. The entire game is focused on survival gameplay, offering dramatically different tropes from traditional FRPGs. Part of that is focused on a large set of pre-defined threats, which combined with a zone creation system allows for the easy framing of stories.

This is all wound up with an evocative background and lavish, well-produced books, producing a world that proved exciting for players even before they got to the dynamic game system.

As a whole, Mutant: Year Zero has redefined the post-apocalyptic gaming space. It’s one of the major forces in the return of post-apocalyptic roleplaying to the mainstream spotlight, something that hasn’t been true since the decline of the Cold War reduced the spectre of WWIII-fears and pushed real-world-setting games like Twilight: 2000 (1984) to the sideline. For over a decade afterward, the post-apocalyptic space had been largely filled with nostalgic offerings like the d20 Gamma World (2003) and the B/X Mutant Future (2008). That was only changing with the release of Apocalypse World (2010), which brought indie sensibilities to the genre and was another mainstream hit. Mutant Year Zero would brought those indie design ideas further out into the mainstream, with plenty of new twists of its own.

The Year Zero system has also been successful enough that it’s allowed Fria Ligan to create a whole series of Year Zero-based games, from the retro/legacy play of the FRPG Forbidden Lands (2018) to the noir future of Blade Runner (2022). Meanwhile, Mutant Year Zero has already been made into a “tactical adventure game”, Road to Eden (2018).

Like Target Games before it, Fria Ligan is now going from strength to strength. Unlike Target Games, they’ve been able to break into the international and English-language market. As a result, they’ve gained a reputation as one of the top RPG producers of the modern-day. That’s ultimately thanks to the strong game design of Mutant: Year Zero and its almost pitch-perfect depiction of a gritty, post-apocalyptic landscape.

N is for Nobilis

Ron Edwards usually gets the credit for kicking off the modern indie movement, not necessarily because of his work on Sorcerer (1996, 2001), but because of his efforts developing the indie community at The Forge and at conventions, enabling the collaboration that led to many of the indie industry’s advances over the next decade.

But James Wallis was publishing equally important indie books at Hogshead Publishing through his “New Style” line, beginning with The Extraordinary Adventures of Baron MunchausenPuppetland (1999) and Michael Oracz’s epistolary RPG De Profundis (2001). Most of the New Style RPGs were short, simply produced books, but Wallis ended his indie work with something entirely different: Jenna K. Moran’s Nobilis (2002).

Nobilis is a game of conceptual demigods who represent ideas such as war or peace or even more concrete elements such as chocolate or music. In an urban fantasy of the modern day, they fight against the Excrucians, who come from beyond and seek to rebuild reality. It’s a “The World is a Lie” setting of the sort that was popular in the ’90s, also seem in games such as Kult (1993) and Mage: The Ascension (1993). However here, the high concept is beautifully portrayed through Moran’s poetic voice.

The game system of Nobilis also shines. As a diceless gaming system about superhuman entities, it primarily followed in the footsteps of Amber Diceless Role-playing (1991): the demigods of Nobilis could largely do what they wanted when engaging in mortal affairs, with the scant resource of miracle points allowing them to sometimes engage in even greater activities. But where Amber largely saw these greater activities as conflictive, as was appropriate for Roger Zelazny’s Amber novels, Nobilis focused more on the question of consequences. To use the language of improv actors, Nobilis is a game of “Yes, and …”. You can do what you want, but what are the results? It’s a far cry from the stories of strife that have underlay the RPG hobby since D&D (1974), and it shows how much RPGs can vary from that original foundation.

Nobilis was actually originally produced in a small print run by Pharos Press (1999). But it was Hogshead’s 2002 edition that broke the game into the mainstream. Hogshead’s massive coffee table book was beautifully produced with gorgeous art and sidebars full of flash fiction about the setting. It’s called the Great White Book and is one of the holy grails of roleplaying collecting.

Nobilis was more recently reprinted in a two-volume set by EOS Press (2011, 2012), but seems to be entirely out-of-print today — though fortunately both the second and third editions remain available through DTPRG. It remains an innovative and groundbreaking game, both for its beautiful modern mythology and its thoughtful gameplay.

O is for Og: The Roleplaying Game

Aldo Ghiozzi started Wingnut Games as a joke. His debut game, Phart! The Dispersing (1994) was obviously a joke too, as was Og (1994), the game of caveman combat. Carrying on the trend, when Ghiozzi transformed his beer & pretzels caveman wargame into Og: The Roleplaying Game (1995) that was a joke too.

Much like HōL (1994), OgOg also contains one mechanic which is entirely innovative: language.

There are only 17 words in Og: you, me, rock, water, fire, tree, hairy, bang, sleep, smelly, small, cave, food, thing, big, sun, and go. Most cavemen know just a few of them. That means that communication is Og is severely limited.

This was particularly innovative in two ways.

First, it brought the humor out of the rulebook and into the game. It’s easy enough to put funny text in a book, or to give funny names to things in a game. It’s much harder to encourage GMs to create funny situations or to encourage players to be funny in games. But making it hard for people to communicate: that’s a pretty sure-fire route to humor. It turns a silly RPG into a funny RPG.

Second, it put a limitation on the main interaction in roleplaying games, which is of course communication. That was an excitingly different way to look at roleplaying games, totally separate from the indie revolution that would be shortly kicking off.

A game can be quite innovative without necessarily being influential, and that’s likely the case for Og. There hasn’t been anything else that’s tried to limit communication quite as much. But, there have been any number of games limit the medium of communication, which can be an equally big change. Thus, you have the index cards of Microscope (2011) and the maps of The Quiet Year (2013), though those are admittedly backed up by as much freeform conversation as you want. But you also have the letter writing of De Profundis (2001) and the text messaging of Alice is Missing (2020), both of which impose much tighter strictures on communication.

A lot of innovation in roleplaying games in the last few decades has come in new sorts of mechanics, in new levels of player agency, in new divisions of authority. Innovating instead on new sorts of communication is very different, and Og trailblazed that ground.

Several years after Wingnut published Og and reprinted it as Land of Og (2000), Robin Laws produced a licensed version for Firefly Games called Og: Unearthed Edition (2007). One of the dangers in a funny game is always making sure it’s playable: Laws worked to push Og more toward playability.

P is for Paranoia

In the early ’80s much of the industry was still producing material that was a reaction to Dungeons & Dragons (1974). But here and there, games were starting to appear that modeled gaming in different ways. Much of that was genre emulation: games created to model works of fiction or genres of storytelling. Four in particular stand out as predecessors to storytelling games and the indie revolution that would follow: James Bond 007 (1983), King Arthur Pendragon (1985), and Ghostbusters (1986) all chose specific, extant properties to emulate. And then there was the dark, dystopic SF RPG Paranoia (1984), one of the most original RPGs produced in the industry’s first decade.

To a certain extent, Paranoia could be said to be returning to the industry’s origins. After all, it created the highest level of PvP (Player vs Player) conflict since dungeon delvers had squabbled over treasure in very early D&D games. It amped up the role of the gamemaster as a diabolic foe, not a friendly narrator.

But it did all of this in service to a very specific world view, where no one could be trusted, where you really did have to keep your laser ready. It was twisted darkness in a time when roleplaying games were just for fun. Through the carefully considered creation of a realm ruled by an insane AI, where secret societies and mutations were illegal yet everyone was a member of a secret society and a mutant, Greg Costikyan, Eric Goldberg, and Dan Gelber created a masterpiece. Paranoia‘s Alpha Complex is a setting that would have been ranked right up there with its dystopic influences such as A Clockwork Orange and 1984 if it’d been a work of fiction, but as a game that gave players the opportunity to experience wrongthought, catch-22s, and all the rest, it was even more wonderful.

Paranoia was social satire disguised as roleplaying game. A decade before HōL (1994), it was a parody of roleplaying itself. Paranoia may have been the first roleplaying game designed to make players truly think, not necessarily about the game, but about what it said about the real world and about their hobby.

As with most humor games, full support of Paranoia required magnificent adventures. They had to highlight the misery, misanthropy, hopelessness, and humor of Paranoia in ways that individual GMs might not be able to. Paranoia fully accomplished that goal. John M. Ford’s The Yellow Clearance Black Box Blues (1985) is usually considered the game’s early masterpiece, but every player probably has their own favorite memories of the impossible situations they were confronted with and how they killed their friends and ultimately themselves as a result.

For a long time, Paranoia was criticized because it was brilliant for a one-off session, but just too exhausting to play as a campaign. Ironically, that was one of the ways that Paranoia foreshadowed the future. The indie movement showed us that games don’t need to turn into campaigns: you can have perfectly wonderful one-off roleplaying experiences.

Paranoia was there first.

Nothing is said here about the game system, and really the early Paranoia game mechanics weren’t of particular note (though the second edition cleaned things up enough to let everything else shine). It was the setting and the adventures and the games that they enabled that really made Paranoia great.

The brilliance of Paranoia was so great and so unique that it was hard to maintain. The parody and self-referential satire slowly changed to broader genre satire, the introspection transformed into slapstick. There were was no third edition. There was no fourth edition. There very definitely was not a fifth edition. The whole game fizzled out in the ’90s (along with its original publisher).

Fortunately there have been several revivals in the 21st century courtesy of Mongoose. Following a successful 2022 Kickstarter, the “Perfect Edition” is due out this year.

Q is for The Quiet Year

The Quiet Year (2013) was a product of the mature indie scene that had developed by the ’10s. It featured many of the tropes that had developed through the Forge, all well-polished into a tight, easy-playing game. It’s a single-session game where players chart out the story of a post-apocalyptic community over the course of a year, prior to the arrival of “The Frost Shepherds”. There’s no GM, with story guidance instead provided by a deck of cards.

There’s some neat innovation in The Quiet Year. The card play nicely correlates with the 52 weeks of “The Quiet Year”, offering both inspiration and latitude for creativity. There’s also some real focus on the community, allowing the players to develop it through projects using simple game mechanics.

That community was part of the real innovation of The Quiet Year. Out the same year as Microscope (2011), The Quiet Year also demonstrated that indie games could be about larger stories of places, not just people — though the concept actually predates the indie scene, going back to at least Aria (1994), a classic game of community and world building that was unfortunately anchored in the complexity of ’90s design rather than the new ideas of the indie community. (Aria as a result may have been the game with the worst buy-to-play ratio ever.)

The Quiet Year had one other major innovation, an idea that was (almost) wholly original: map-drawing play. Players sketch out the community at the heart of their story and modify that drawing over time as they begin and fulfill projects. The map becomes an alternate method of communication (quite different from verbal back-and-forth of a typical RPG), a focal point for attention, and also a source for new ideas. It helps to anchor the storytelling of the narrative indie, ensuring that players aren’t at sea, because they always have something to hold on to.

There was at least one prior game that included some aspects of map-building, Archipelago (2007), but it only really pushed on those ideas a year later, in Archipelago III (2012). And, that’s been a relatively rare follow-up to The Quiet Year. Despite the innovation of the game’s map-drawing play, just a few other games have followed on with map-building of their own, among them spinoffs such as The Deep Forest (2014) and other RPGs such as Companions’ Tale (2018). Most of the other RPGs more fully mix the map-building with character-based play. The Quiet Year thus remains a fairly unique RPG, in a class all its own.

The Quiet Year reminds us that RPGs can be very different. That they can tell much bigger stories, such as the tale of a community, and that can be just as intriguing as the intricacies of human behavior. It’s an innovation well worth considering.

R is for RuneQuest

It’s hard to believe now, but in the primordial days of the roleplaying hobby, there was still a belief that other, newer RPGs might unseat Dungeons & Dragons (1974) as the genre leader. Two fantasy RPGs thus rose to considerable heights in that first decade: Tunnels & Trolls (1975) and RuneQuest (1978).

RuneQuest was published in an era when the scant FRPGs on the market, from Tunnels & Trolls through Chivalry & Sorcery (1977), were mainly responses to D&D. They reiterated ideas of classes and levels and they repeated tropes of play like engaging in warfare, killing monsters, and looting dungeons. It was a trend that would not only continue for a few more years, but then would repeat in the ’90s with the advent of the Fantasy Heartbreakers.

RuneQuest was something entirely different.

That was in part due to the fact that RuneQuest entirely eschewed the class-and-level norms created by D&D. The previous year, Traveller (1977) had been the first RPG to widely adopt the idea of skills as the foundation of its play, and now RuneQuest both took them further (through the ability to improve skills during play) and brought them to fantasy RPGs. Steve Perrin’s game system was a notable innovation in game design at the time and offered a type of fantasy play that hadn’t previously been available on the market.

But where RuneQuest really excelled, and set a notably high bar for RPGs in the decade to follow, was in its depiction of Greg Stafford’s world of Glorantha, which had previously been introduced in the wargame White Bear and Red Moon (1975).

To start with, Glorantha was a fully described and imagined world, in a time when The City-State of the Invincible Overlord Playing Aid (1977), The Wilderlands of High Fantasy (1977), and The First Fantasy Campaign (1977) were the only attempts to publish settings for use by the gaming public. But where all of those settings were produced as add-ons to the D&D game, RuneQuest instead incorporated the setting of Glorantha directly into its rules, making it one of the first attempts at genre emulation in gaming, alongside Chivalry & Sorcery and its more authentic medieval design, but raising that genre-focused game design up to an even higher level.

The idea of genre emulation would achieve even greater heights in the ’80s through releases such as James Bond 007 (1983), Paranoia (1984), King Arthur Pendragon (1985), and Ghostbusters (1986) — the latter two designed and co-designed by Stafford, respectively. In RuneQuest, that genre emulation could be found in game elements such as its battle magic and divine magic, its rules for interacting with spirits, and its strange set of creatures such as baboons, broo, dragonewts, and ducks. Together they suggested a world very different from the pseudo-Medieval fantasy of D&D, C&S, and others.

To be precise, Glorantha was a world of mythology, where gods touched upon the realm of mortals, and where mortals encouraged those connections through cults. It was a world where heroic paths of the past resonated into the present as heroquests. Much of this would be revealed through later publications such as Cults of Prax (1979) and Cults of Terror (1981), which were themselves just as groundbreaking as RuneQuest itself, for their deep depictions of the cultures and myths of a fantasy world.

RuneQuest only grew in power and popularity throughout the early ’80s, especially in the UK where it was given special support by Games Workshop. It spawned a whole series of Basic Roleplaying (BRP) games, the most famous of which is Call of Cthulhu (1981). It originated the entire game design scene in Sweden, which has in turn resulted in modern-day companies such as Fria Ligan. There can be no doubt that RuneQuest has been deeply influential in a way that few games other than D&D itself were.

But, RuneQuest also survives into the modern-day as a going concern, thanks to a reinvigoration of its publisher, Chaosium, that occurred in the ’10s. The newest edition, RuneQuest: Roleplaying in Glorantha (2018), polishes classic systems for the modern-day while adding on new innovations such as a lifepath chargen system and emotional passions borrowed from Pendragon. As the name of the newest edition indicates, the innovative and evocative world of Glorantha is more central to the game than ever before, highlighting the greatest strength of this long-lived game.

S is for Savage Worlds

The heyday of universal roleplaying was in the ’80s and ’90s, when GURPS (1986) was young and the entirety of space and time was being plundered to provide grist for its supplement mill. But in the ’00s, a new universal game system arose: Savage Worlds (2003).

Savage Worlds actually grew out of the weird-western RPG, Deadlands (1996) via The Great Rail Wars (1997), a cut-down version of the original system used for miniatures play. Six years on Shane Lacy Hensley developed it into a new universal system. Savage Worlds‘ first settings were far-flung from the Wild West, including the fantasy Evernight (2003) and the swashbuckling 50 Fathoms (2003), showing from the start the new system’s breadth.

Though Savage Worlds was a universal system, it had a particular point of view. It was a pulpy, action-oriented point-of-view, as evidenced by the game’s slogan, which was “Fast! Furious! Fun!” In other words, while GURPS ruled the universal roost in the 20th century because it was a master of simulation design, Savage Worlds did the same in the 21st century because it was a master of emulation design.

Savage Worlds‘ foundation nonetheless is a well-designed simulation, with point-based character generation, including edges and hindrances, and a universal task resolution system measured against a set target number. However Savage Worlds really shines, becoming action-adventure emulation rather than mere simulation, due to a number of nuanced add-ons to the system.

Initiative is managed with playing cards, which speaks to the game’s Deadlands origins, but also puts players right into the mindset of bids, bets, and bluffs. Wild dice give PCs and select NPCs an extra (advantage) die, making them more powerful and lucky in the face of masses of mooks. Dice explode when the maximum number is rolled, and the higher a success climbs, the more “raises” accrue, culminating in exciting (and spectacular) results. When all else fails, bennies give players agency, allowing them to avoid damage, reroll results, or activate edges. It’s a cinematic game of action, with larger-than-life heroes and villains who seem invincible … until snake eyes are rolled!

Savage Worlds excels not just because of its beautifully crafted game system, but also because of the quality of its settings. It started with Evernight, a post-apocalyptic fantasy world of resistance and rebellion where the baddies had won, and 50 Fathoms, the story of a drowned world following a different sort of apocalypse (and the age of piracy that resulted). They were followed by the supervillains of Necessary Evil (2004), the Weird Wars (2005+), the return of Deadlands (2005), and much more.

50 Fathoms also brought in a new concept that would be one final feather in Savage Worlds‘ cap: the Plot Points campaign. These were metaplots for entire campaigns, but laid out as individual “Savage Tales” that players could visit as they saw fit, creating adventure-sandboxes rather than the adventure-paths typical of the era.

Much like the simple Savage Worlds system, and its support through accessories such as playing cards and bennie (Poker) chips, the plot point system of Savage Worlds made the game easy to run. That was another way that Savage Worlds was a next-generation roleplaying system. It wasn’t just the change from simulation to emulation, but the realization that RPG players were no longer necessarily students with all the time in the world, but often professionals who wanted to run games, but had limited time to do so.

Savage Worlds is a perfect reflection of the changing face of gaming a generation on.

T is for Torg

It began with an advertising campaign from West End Games that kept roleplaying fans on the edge of their seats for months. “A New Roleplaying Game Experience” the mottled ads said. And then, simply, “Torg”. Gamers wondered what it could be, enthusiasm mounted, and finally Torg (1990) appeared, by Greg Gorden with Douglas Kaufman, Bill Slavicsek, Christopher Kubasik, Ray Winninger, and Paul Murphy.

Torg, it turned out, was a multigenre roleplaying game. It was the next evolution of the universal RPGs like GURPS (1986) and Hero System (1990) that were increasingly dominating the industry. But where the universal systems allowed one game system to be used for many games with many different genres, the multigenre RPGs instead allowed one game system to be used for many genres all within one game! It was clearly an idea that was in the air because Kevin Siembieda released Rifts (1990) the same year. But where Rifts was based on a complex, old-school system that traced its origins back to D&D (1974) itself, Torg was a much newer take on roleplaying.

The setting of Torg itself was innovative. Multiple “cosms” had intruded on Earth. Thus the Nile Empire provided a cosm of pulp adventure, Orrorsh one of gothic horror, and the Cyberpapacy melded the then-popular cyberpunk genre with religion. But Torg went beyond just creating a simulation of characters that could be used in these various genres. It also simulated those alternate realities themselves, with each having different axioms measuring Spirit, Magic, Social, and Technology.

Torg‘s core resolution system using dice and a chart, a concept that would very quickly fade from the industry. But it also incorporated the “drama deck”, a new methodology for player agency designed by Ray Winninger. Not only did these cards add color to conflicts on a round by round basis, but they could also be saved by players as a resource, allowing dramatic success and new storytelling opportunity for players.

Torg‘s mechanics of axiom simulation and player agency through storytelling are the sort of thing that can slowly move a universal simulation toward genre emulation, meaning that Torg lay square on the path between GURPS and Savage Worlds (2003). But even that wasn’t the extent of its innovation.

Torg also featured what may have been the industry’s most interesting take on metaplot — an idea that would gain ground in the ’90s primarily due to Vampire: The Masquerade (1991) and the World of Darkness. Metaplots allowed a setting to slowly change over time, typically through the release of new supplements that advanced a plotline. But West End instead decided to (once more) give agency to its players. They published a newsletter called Infiniverse (1990-1994) that players could use to report the happenings of their own campaigns. West End then averaged out all the results and used those as the foundation for the official storyline of the cosms’ war upon Earth. A number of Campaign Game Updates (1992-1994) reprinting the Infiniverses were eventually followed by War’s End (1995), a first of its kind true-finale to a game setting.

Beyond Torg‘s own innovations, the game also continued to have a strong impact on West End afterward, as it was the foundation of their “MasterBook” house system, which was the basis of a variety of new RPGs from 1993-1997.

Torg has since been resurrected, most successfully by Ulisses Spiele, who published Torg Eternity (2017) as well as an extensive line of sourcebooks, the newest of which, the Pan Pacifica Sourcebook (2023) has just shipped.

Oh, Torg also had a really attractive mottled blue and red d20. Gorgeous!

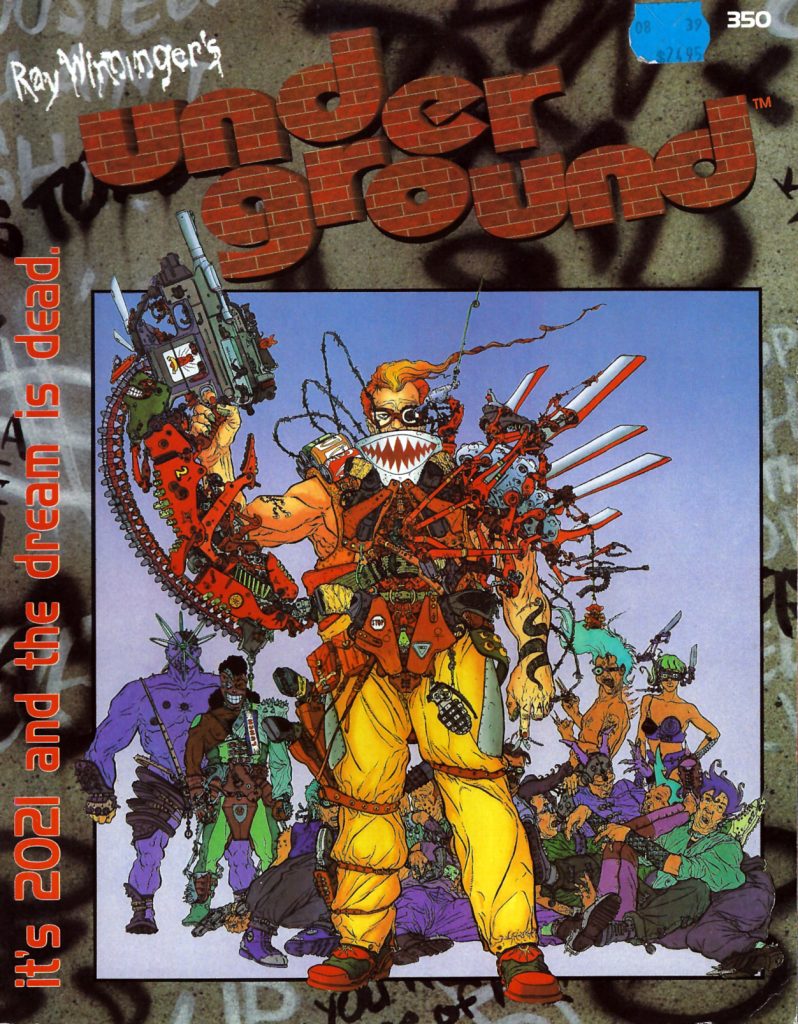

U is for Underground

If there is a roleplaying game that was a perfect reflection of its time in history, it’s probably Ray Winninger’s superheroic RPG Underground (1993).

It was the ’90s. As the world grew dark and gritty, Image Comics was ascendant. Superheroes sprouted guns and pouches. Anti-heroes became the soup-er de jour. It was the era of Cable and Deadpool, Doom Patrol and The Maxx, Darkhawk and The Savage Dragon. And especially it was the era of Marshal Law, a murderous government-sanctioned hero. Ray Winninger captured his own impression of the era with Underground, a roleplaying game of genetically re-engineered corporate army vets, afflicted with PTSD from their powers, returned home to become vigilantes.

But Winninger went far beyond the tropes of superhero comics by also incorporating the punk and anti-corporate themes of the cyberpunk genre. His Underground was a satiric critique of modern society that today feels eerily prescient, a new Paranoia (1984) for the ’90s, but with a harder edge. In Underground’s America, corporations have grown wild. They have taken over the country and are rewriting the Constitution. They’ve bred a workforce of low-intelligence workers and are literally using people as the grist for their corporate mills. Meanwhile, there’s a Second Cold War going on, and it’s all about economic power.

There’s nothing attractive about Winninger’s vision of corporate America gone wrong. In fact, it’s pretty ugly — and that’s what makes Underground so beautiful. It portrays that grotesque future exactly so that we can assess what sort of world we want to live in. If there was a statement RPG of the ’90s meant to prompt conversation while still allowing actual roleplaying, it was Underground.

There’s a surprising ray of light in all of this darkness and ugliness, and it’s the heroes. They’re members of a community – which is an actual entity with the campaign, with its own stats. They’re trying to make that community better, both by increasing its Parameters and by meeting their Campaign Goal. But any improvements are like dust in the wind, constantly shifting underfoot.

Besides its innovative setting and thoughtful satire, Underground also had an innovative layout: “hypertext” sidebars contained trivia and other fun information, while color-coding made it easier to find content. The full-color rulebook was one of the first in the industry.

Underground clearly falls into the same category as other dark parodies such as Paranoia (1984) and HōL (1994). It would likely have reached similar levels of acclaim in the industry if not for the fact that publisher Mayfair began moving out of the roleplaying field shortly after its publication. As a result, it’s a lesser-known masterpiece than those others, with their long support from West End and White Wolf, respectively.

The Underground game system also deserves a brief note. It’s based on DC Heroes (1985), which had one of the most intriguing simulation ideas ever: one unit within the game is always symmetric. So a unit of strength lifts a unit of weight. Four units of speed over one unit of time cover five units of distance. How well that system worked, especially given conversions and the exponential scale required by the original DC Heroes (tuned somewhat downward here), remains a question for individuals, but it’s nonetheless an amazing world-model.

Today it’s 2023, just two years past the future history of Underground in 2021. It’s sobering to ask how much of Ray Winninger’s vision has come true.

V is for Vampire: The Masquerade

After D&D (1974) itself, the most inspirational and influential game in the industry is likely Mark Rein-Hagen’s Vampire: The Masquerade (1991). At the time, Mark Rein-Hagen was fresh off of his debut work on Ars Magica (1987). The White Wolf game company represented a new partnership for him, and that’s often the prime ingredient for creativity — as was the case here.

It started on the road to Gen Con ’90, when Mark Rein-Hagen and fellow White Wolfers Stewart Wieck and Lisa Stevens hit upon a great idea for a new game. It would be dark and moody, it would be the first in a series of linked RPGs, and it would inherit some history from Ars Magica itself. It was to be a game of modern-day vampires, possibly even a licensed game based on Anne Rice’s Vampire Chronicles.

And the players would take on the roles of those vampires.

Arriving at Gen Con, the White Wolf crew were confronted with Stellar Games’ own urban monster game, NightLife (1990), and that almost brought the nascent project to an end. But NightLife was lighter than what they planned: the White Wolf designers knew that they were going to do something very different.

In fact, Vampire: The Masquerade would be quite different from anything else in the industry. It would obviously be a far cry from the fantasy games that ruled the industry and the science-fiction games that took up the second rank — and at the time were deviating toward the cyberpunk subgenre. Vampire: The Masquerade would be quite different from not just NightLife but also the then-ruler of the horror RPG category, Call of Cthulhu (1981).

That was in part because of the mood of Vampire: The Masquerade. White Wolf focused on gothic stylings for the game, something that had been seen just once before in the industry, in TSR’s Ravenloft (1983). But those gothic stylings weren’t just window dressing. They encompassed the whole game. That began with the vibrant and evocative cover to Vampire, with its rose on a green marble background. It continued inside the book with setting-based fiction and with stylistic black & white art by Tim Bradstreet (and over time many others). The result was a sort of immersive reality that the industry had not previously seen.