When we Kickstarted Designers & Dragons, we gave three patrons the opportunity to suggest topics for me to write about. This is the first of them, courtesy of Janelle Cooper, Jacq Jones, and the Women & Gaming Forum of BGG.—SA, 8/4/15

This article was originally published as Advanced Designers & Dragons #4 on RPGnet. It was written for inclusion in Designers & Dragons: The Platinum Appendix (2015).

Although the roleplaying industry has had a well-deserved reputation for being male-dominated since its earliest days, women have always been involved as players, as writers, as designers, and in a variety of other roles. Through the decades, their impact and involvement has grown and evolved.

Female Players in the Industry: 1974-1979

Before looking at the role of women in the roleplaying industry, we should first consider the role of women in roleplaying — especially in its earliest days.

RPG historian Jon Peterson began his own look at the topic with a reminder that roleplaying evolved from an extremely male-dominated hobby: miniatures wargaming. Peterson says that Strategy & Tactics (1967-Present) surveys showed as few as 0.5% of wargamers were female. This was the state of the industry when Dungeons & Dragons (1974) first appeared.

Though it evolved from wargaming, roleplaying offered something in addition to warfare. Its focus on individual characters appealed to a wider variety of players, including more women. Gary Gygax, in The Dragon #22 (April 1979), opined that “at least 10% of the players are female!”

However, surveys, referee lists, and con attendance from the period show lower numbers than Gygax’s estimate, as reported in Shared Fantasy: Role-Playing Games as Social Worlds (1983), Dr. Gary Alan Fine’s analysis of the young roleplaying industry. Among the earliest contributors to the roleplaying industry, The Space Gamer offered the lowest estimate of female fans, with just 0.4% of its respondents (two people) being women — but unlike many of its contemporaries, The Space Gamer maintained a strong focus on science-fiction and fantasy wargames, not RPGs, which may explain the difference. A Judges Guild survey reported 2.3%, while Fine estimated that 3.8% of players from a referee’s list in The Dragon were women. Finally, con attendance records showed that about 5% of attendees at Origins ’78 and a contemporary Gen Con were women.

I offer three explanations for women’s lack of involvement: characteristics of women; the process of recruitment into the gaming world; and reactions of men to the presence of women and female characters in the gaming scenario.

Gary Alan Fine, Shared Fantasy: Role-Playing Games as Social Worlds (1983)

The precise numbers of female players probably lay somewhere between the estimates of Gygax and Fine. Women playing at the time report that magazine subscriptions were sometimes in the names of their husbands or children, which might have led to them not participating in those magazines’ surveys, and that they often stayed home with children while their husbands attended a convention. That leaves us with an estimate of female players being between 5% and 10% of all roleplayers in the late ’70s.

So what did that mean for women in the industry?

Female Pioneers in the Industry: 1975-1986

Lee Gold was the industry’s first female star and in the ’70s she was one of the ten or so most important people in the roleplaying field. She’d been a science-fiction and fantasy fan since junior high, then joined the roleplaying hobby in 1974 when her friends — Owen and Hilda Hannifen from San Francisco — shared their copy of D&Dwith her.

The Hannifens and Gold were all members of the Amateur Press Association (APA) of the Los Angeles Science Fiction Society. The Hannifens soon began sharing stories about Dungeons & Dragons here, but non-roleplayers in the APA asked the D&D; enthusiasts to start up a distribution of their own. Meanwhile, Gold was worried about the increasing divergence between different groups’ D&D; games and the “culture shock” that it could cause if someone tried to join a new group. These factors led Gold to start Alarums & Excursions (1975-Present), an APA that freed the Science Fiction Society from talk of D&D; and gave gamers the opportunity to form a culture around the game.

A&E; was a milestone in the history of roleplaying. With its publication in June 1975, it became the earliest periodical solely dedicated to roleplaying games — predating even TSR’s Dragon (1976-2007). It’s also the most long-lived roleplaying periodical, having missed just two months of publication in almost 40 years. Over those years, A&E; has featured a lot of all-star contributors, including Gary Gygax, Edward Simbalist, Wilf Backhaus, Dave Hargrave, Steve Perrin, Jonathan Tweet, Robin D. Laws, and Rob Heinsoo. It deserves a history of its own, and that’s thanks to Lee Gold.

When I was a girl, I had Chainmail

Lee Gold, Filker Up #6 (2009)

And a three-book boxed D&D; set,

And I used all the Platonic solids

To determine what monsters I’d get.

Jennell Jaquays didn’t face the same challenges entering the RPG field as Gold, because at the time she was writing under the name Paul Jaquays. Nonetheless, today we can recognize her as another influential woman in the early industry. She started out by creating The Dungeoneer (1976) magazine, where she wrote some of the industry’s earliest adventures. She then authored numerous groundbreaking works for Judges Guild and Chaosium starting in 1979. Like the other women of the time, she offered a unique perspective on the industry.

Though Gold and Jaquays entered the industry on their own, Dr. Gary Alan Fine’s studies suggest that, in the ’70s, the majority of women were recruited into roleplaying by a husband or boyfriend. Similarly, many of the earliest female designers appeared in the industry as the co-authors of books written with a significant other.

The earliest of these co-authored books were all third-party D&D; supplements. The Character Archaic (1975), and early adventures Palace of the Vampire Queen (1976) and The Misty Isles (1977) were co-authored by Judith Kerestan of Wee Warriors; Quest for the Fazzlewood (1978), published by Metro Detroit Gamers, was co-authored by Laurie Van De Graaf; Rahasia (1979) and Pharaoh (1980) by DayStar West Media were co-authored by Laura Hickman, who also contributed to a few later TSR projects; Carse (1980) and Jonril (1982) from Midkemia Press were co-authored by April Abrams; and The Dragon Tree Spell Book (1981), The Handbook of Tricks and Traps (1981), and a few others from Dragon Tree Press were co-authored by Mary Ezzell.

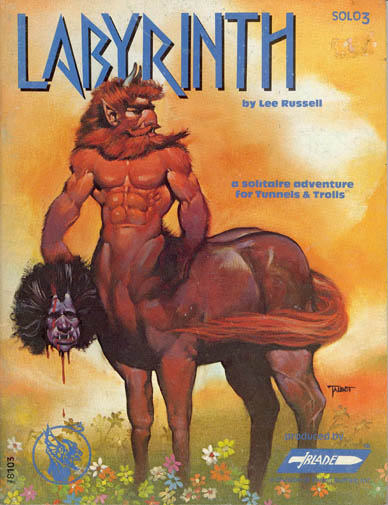

The first major roleplaying supplement authored entirely by a woman appears to be Flying Buffalo’s Tunnels & Trolls Solo Adventure #3: Labyrinth (1978), by Lillian “Lee” Russell. Flying Buffalo was one of the earliest roleplaying companies to reach out to female designers; Liz Danforth joined the company in 1978 as an editor for Sorcerer’s Apprentice magazine (1978-1983). Over the next five years, Flying Buffalo’s magazine largely represented her vision.

As the ’70s faded into the ’80s, women designers moved from producing supplements to producing roleplaying games of their own. Liz Danforth’s fifth-edition update of Ken St. Andre’s Tunnels & Trolls (1979) marked a major revamp of the rules that would be the standard for decades thereafter. Supergame (1980) was co-written by Aimée Karklyn and her significant other.

Lee Gold pioneered the way for female solo design with two roleplaying games. Land of the Rising Sun (1980) was based on the rules from Chivalry & Sorcery (1977), but the historical Lands of Adventure (1983) was a wholly original effort. They were both published by FGU.

A few small press RPGs with female authors arrived in the early ’80s, like Wizards’ Realm (1981) from Mystic Swamp, which was co-authored by Cheryl Duval. However, it wasn’t until deep in the ’80s that more appeared, such as Pacesetter’s Sandman (1985), which was co-authored by Andria Hayday, and Chaosium’s Hawkmoon (1986), a solo effort by Kerie Campbell.

These early roleplaying designs were somewhat unusual for the industry at the time. Not only did they feature relatively few monster-bashing dungeon crawls, but Gold’s RPGs included one of the first Asian-influenced fantasy RPGs and an early historical fantasy, while Campbell’s was a licensed science-fantasy game.

Sadly, these games designed and written by women were also quite scarce. It was a sign of the times — a trend that was a reflection of the employee demographics at industry leader TSR.

Female Pioneers at TSR: 1978-1997

It took a few years for TSR to consider female creators, and even then the process began with an external writer: Gary Gygax ran a D&D; game for Andre Norton so that she could write Quag Keep (1978), an unofficial D&D; novel that was the industry’s first.

Things got going at TSR proper late in 1978, when Gary Gygax was thinking about creating an in-house Design Department. He began talking with a potential female recruit: a D&D; player named Jean Wells. Gygax flew her out to Wisconsin in January 1979 and decided she was a good fit; he announced her hire in The Dragon #24 (April 1979).

Though Wells was a D&D; player and a romance writer, she didn’t have any experience with rules design and development. The plan was for Gygax to teach her, but he was too busy by the time she arrived, and Wells was afraid to ask anyone else. This was the first of several obstacles she faced as TSR’s first female designer.

Wells soon ran into another problem: a male-dominated culture. At first other staff members wouldn’t even let her play in D&D; games; when they relented, they initially insisted she play male characters. Unfortunately, this dismissive attitude was still obvious decades later when one of Wells’ former coworkers described her as “large, insecure, brashly outgoing, and outspoken” — a mélange of adjectives that probably would not have been applied to a man.

He was hiring my imagination and would teach me the rest.

Jean Wells, “Interview: Jean Wells (Part I),” Grognardia (2010)

Despite these problems, Wells made a number of notable contributions to D&D; from 1979-1982. She wrote an uncredited section in the Dungeon Masters Guide (1979) and became the original sage of D&D;‘s “Sage Advice” rules column, answering questions from The Dragon #31 (November 1979) through Dragon #42 (October 1980). Her character Ceatitle can be found in the original Rogues Gallery (1980), and she was an editor for several early products, including B2: The Keep on the Borderlands (1981). Her artwork can also be found in a few early publications, including the third (1979) and later printings of the Monster Manual (1977) — which include her drawings of four monsters that had previously been missing pictures: the eye of the deep, the giant Sumatran rat, the otyugh, and (probably) the violet fungi.

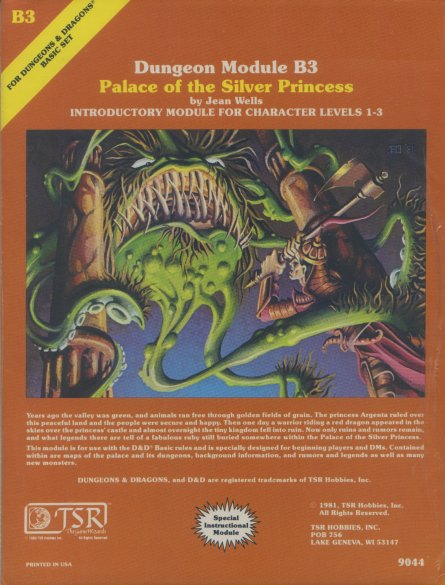

However, for better or for worse, Wells is best known for the original B3: Palace of the Silver Princess (1981), which she prepared with help from editor Ed Sollers. Unfortunately, after it came back from the printers, Lawrence Schick and/or Kevin Blume decided that the module wasn’t acceptable. A number of reasons have been offered over the years. Some claim that it wasn’t edited sufficiently because of Wells’ relationship with Gygax. Others state that it was “mediocre.” Wells said she got called out over S&M; elements (though neither she nor Sollers knew what S&M; was). There were also issues with Erol Otus’ drawings — for his personal interpretation of things in the adventure, for his risqué depictions of those things, and for his inclusion of in-jokes. Whatever the reasons, the printed module was mostly trashed and a new version was produced by Tom Moldvay.

The problems with Palace largely meant the end of Wells’ design career; she was confined to secretarial work. Though she proposed a supplement for Top Secret (1980) called “L.A.S.S.” and created a prototype of a space travel board game, she wasn’t allowed to pursue their further development. Shortly thereafter, Wells married Top Secret supplement author Corey Koebernick and left TSR.

In TSR’s later life, its design staff was almost entirely male, but women were influential at the company in other roles. This was common in the roleplaying industry in the ’80s, where women were credited as editors or managers instead of designers or developers. At TSR, four women involved with book publication in the ’80s proved especially crucial to the future of the company.

Rose Estes worked in advertising at TSR, but came up with the idea for fantasy choose-your-own-adventure books. She was given a green light on the project, and immediately wrote the first four Endless Quest books, beginning with Dungeon of Dread (1982). The books were wildly successful, with the first six books selling millions. James Ward said, “We got more mail about them than about the D&D; game.”

However, TSR was concerned that the Endless Quest books were a fad, so it used their success to diversify, creating an Education Department that was intended to produce classroom modules. This new department was overseen by Rose Estes, James Ward, and new hire Jean Blashfield Black, who had been writing and editing science books since the ’60s. Unfortunately, this new initiative didn’t work out: the Education Department completed three classrooms modules, but couldn’t get them to market. Meanwhile, the Endless Quests books were still selling well in 1983, so the decision was made to put even more focus on books. The Education Department became the Book Department, overseen by Jean Black — though it was still called the Education Department for a while.

Enter Margaret Weis, hired by Jean Black as an editor for the “Book” Department. Weis became involved with Tracy Hickman’s Dragonlance project, which was to be the source of the Book Department’s first novel. Weis felt that she and Hickman could produce better Dragonlance novels than an established author, and Black gave them a chance to audition when TSR’s tiny royalty offers didn’t hook a published author who could properly do the job. On the strength of Weis and Hickman’s sample chapters, Black gave them the job of writing the first Dragonlance trilogy.

Their first book, Dragons of Autumn Twilight (1984), took several months to catch on, but then it became another hit. By this time the Endless Quest books had indeed faded; the series ended with the 36th book, Song of the Dark Druid (1986), but by that time Black was producing best-selling novels. Meanwhile, Weis briefly crossed over into game design, co-authoring Dragonlance Adventures (1987); though TSR produced 13 hardcover books for AD&D; 1e, this was the only one that credited a woman as a major designer.

Black left TSR in 1988, and book editor Mary Kirchoff replaced her as the new head of the department. She’d once been a classmate of Ernie Gygax, but her creative portfolio was even more impressive. She was a former editor of Polyhedron magazine (1981-2004) and the author of a few Endless Quest books starting with Light on Quests Mountain (1983). It was also Kirchoff who found a book called Echoes of the Fourth Magic in the Book Department’s slush pile and was intrigued enough to work with author R.A. Salvatore on a new book called The Crystal Shard (1988). Kirchoff oversaw the Book Department through 1992, by which time its books were regularly hitting best-seller lists. She also wrote a few novels of her own, beginning with Kendermore (1989). She’d later return as Wizards of the Coast’s VP of Publishing from 1997-2004.

Just as the Book Department was taking off thanks to the initial work of Estes, Black, and Weis, TSR’s most influential female employee came on stage: Lorraine Williams. She arrived at TSR in 1985 as a manager and potential investor, but by the end of the year had taken control of the company away from Gary Gygax. She’s received mixed reviews over the years for how she ran TSR. However, for over a decade, from 1986-1997, she was clearly the most important woman in roleplaying.

Many other women played vital roles at TSR in the ’80s and ’90s. Among them were Art Director Ruth Hoyer and editors and project managers like Anne Brown, Michele Carter, Sue Weinlein Cook, Andria Hayday, Dori Hein, Miranda Horner, Julia Martin, Karen Martin (later Karen Boomgarden and Karen Conlin), Anne Gray McCready, Penny Petticord (later Penny Williams), Jean Rabe, Cindi Rice, and Barbara Young.

Though TSR’s in-house designers were mostly men, some of these editors also did crucial design work. McCready was one of the first, writing early adventures like CM5: Mystery of the Snow Pearls (1985), RS1: Red Sonja Unconquered (1986), and GAZ4: The Kingdom of Ierendi (1987). Brown also wrote the occasional book — focusing particularly on Greyhawk, from WGA1: Falcon’s Revenge (1990) to Greyhawk Player’s Guide (1998).

Jean Rabe was even more prolific, contributing to over a dozen supplements for TSR in the late ’80s and ’90s, starting with C6: The Official RPGA Tournament Handbook (1987). She moved on to write over a dozen novels for TSR beginning with Dragonlance’s The Dawning of a New Age (1996). In addition, she ran the RPGA for seven years, edited Polyhedron, and oversaw much of the Gen Con Game Fair.

Some editors never wrote books of their own, but nonetheless contributed extensively to their editorial projects. Andria Hayday, who worked at Pacesetter between two different stints at TSR, offers one example. She provided vital content for two of the earliest AD&D; 2e settings, Ravenloft: Realm of Terror (1990) and Al-Qadim: Arabian Adventures (1992). Her work on Arabian Adventures included overseeing art and design and writing the background material on Al-Qadim, which was moved to the front of the book due to its high quality.

Dori Hein was similarly crucial to the creation of the Planescape Campaign Setting (1994), while Sue Cook contributed to Dragonlance: Fifth Age (1996). Cindi Rice edited the Ravenloft line in its final days and contributed to a few of the last books.

Barbara Young is another of TSR’s best-known editors. She briefly worked at TSR as a game editor from 1984 to 1985, before succumbing to a layoff, but then rejoined TSR in 1987 as an assistant editor to Roger E. Moore on Dungeon magazine. She started with #4 (March/April 1987), then took over as editor with #9 (January/February 1988), a role she kept until #51 (January/February 1995). She was largely responsible for the feel of Dungeon during its first decade of existence. She was also a mentor to Wolfgang Baur, who went on to fame of his own. Young later moved on to become the newest head of TSR’s Book Department. Dungeon had another female editor during its last days at TSR: Michelle Vuckovich.

Although female editors were much more common than female designers at TSR in the ’80s, this began to change in the ’90s, as TSR began taking many more freelance manuscripts, resulting in work from Ann Dupuis, Lisa Smedman, and Teeuwynn Woodruff. But by then the rest of the industry was changing too.

Corporate Heroines: 1980-2000

The rest of the industry largely reflected the situation at TSR in the ’80s and ’90s. Some women were writing roleplaying products — such as Steve Jackson Games author Elizabeth McCoy and West End Games author Jen Seiden, a second-generation employee who followed in her father’s footsteps. Their numbers increased with the decades, with many more entering the field than can be recorded here. Women were also becoming more integral to companies in other roles — some of them quite innovative, such as Sue Grau’s work organizing the Hero Auxiliary Corps to support Hero Games.

Women’s importance to the industry was also reflected by an increasing number of women helping to found companies, either as executives or as foundational members. Women were instrumental in founding companies from the beginning, but in the ’70s and the early ’80s, it had been more common for women to create companies with their significant others: the Kerestans founded Wee Warriors (1975), the Hickmans founded DayStar West Media (1979), the Abrams were among the founders of Midkemia Press (1979), and the Ezzells founded Dragon Tree Press (1981). By the ’80s, the “significant other” effect was fading in gaming groups and throughout the roleplaying industry.

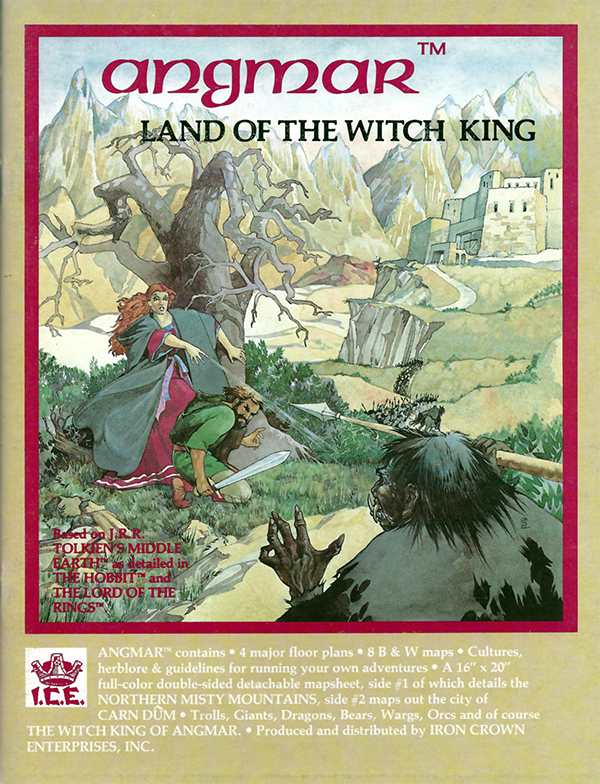

ICE (1980) led the way for this new type of gaming company: Heike Kubash was one of its foundational members. She also co-authored the company’s first Middle-earth sourcebook, Angmar: Land of the Witch King (1982), then wrote their first Middle-earth adventure book, Bree and the Barrow Downs (1984). Many years later she was President of Mjolnir, the second incarnation of ICE, and the co-author of HARP: High Adventure Role Playing (2003).

Perhaps Middle-earth’s familiarity outside of gaming made it feel more welcoming for women, because several others followed Kubasch: Brenda Gates Spielman wrote Umbar: Haven of the Corsairs (1982), Susan Tyler Hitchcock authored Southern Mirkwood: Haunt of the Necromancer (1983), and Jessica M. Ney worked on several projects from 1988-1993.

Other companies followed in ICE’s footsteps. Janet Trautvetter was one of the founding members of Gamelords (1980), where she contributed to The Free City of Haven (1981) and many others. Kristie Fields, Patty Fugate, and Nancy Parker were all founding members of Digest Group Publications (1985). Pacesetter (1984) was one of the more notable RPG start-ups of this period for its high level of professionalism; we’ve already met one of its founding designers, Andria Hayday — the co-author of Pacesetter’s Sandman and a mover and shaker at TSR.

Though Jonathan Tweet and Mark Rein•Hagen created Lion Rampant (1987), Lisa Stevens and Nicole Lindroos were early volunteers. These two then became founding members of White Wolf (1990), and later went on to even more important roles in the industry.

White Wolf deserves additional comment, in part because its LARPs, such as The Masquerade (1993), are widely credited with increasing the number of women participating in roleplaying games. White Wolf also employed a comparatively large proportion of female designers over the years — by the ’00s their online writers’ bios included 11 women out of 28 total designers.

Many women moved through the design halls of White Wolf. Kathleen Ryan was an author and graphic designer for Mage: The Ascension (1993). Jackie Cassada and Nicky Rea were frequent authors and also the line editors for Changeling: The Dreaming (1995) and White Wolf’s Ravenloft (2002). Similarly, designer Jennifer Hartshorn line edited Vampire: The Masquerade (1991) and Wraith: The Oblivion (1994), while designer Deird’re Brooks line edited WarCraft: The Roleplaying Game (2003). Genevieve Cogman was one of the authors of Orpheus (2003), while Heather Heckel, Angel Leigh McCoy, Deena McKinney, and Cynthia Summers all contributed to core White Wolf rulebooks. Other White Wolf authors include Elizabeth Ditchburn Dew, Heather Grove, Sheri M. Johnson, Ellen Kiley, Judith McLaughlin, J. Porter Wiseman, and Lindsay Woodcock. In the modern era, authors like Dana Habecker and Jess Hartley continue the trend.

Three other companies from the ’90s deserve special note in this history of women in the roleplaying industry.

First, Wizards of the Coast (1990) brought on Lisa Stevens as their first paid employee after her stints at Lion Rampant and White Wolf — a reflection of the industry experience she’d by then accrued. Stevens was a crucial member of the Wizards team in the ’90s, suggesting early RPG acquisitions like Talislanta (1987) and Ars Magica (1987) and later becoming the brand manager of TSR properties like the RPGA, Greyhawk, and the d20 Star Wars game.

Second, Grey Ghost Press (1995) was created by former TSR freelancer Ann Dupuis. It was the first major roleplaying company founded solely by a woman — and an important one because it introduced FUDGE (1994) to a much larger audience. As a result, some now call Dupuis “the founding mother of indie gaming.”

Third, Sovereign Press (1998) was co-founded by Don Perrin and Margaret Weis — who later revamped the company as Margaret Weis Productions (2004). The fact that Weis has enough recognition that her name is a draw shows how much things have changed since the ’70s.

From ICE to Sovereign Press, women were more important than ever to roleplaying companies, and that trend would only improve in the ’00s.

The Modern Woman: 2000-Present

The roleplaying field still has a long way to go before it becomes gender balanced. Wizards of the Coast did a survey of 20,000 households in 1999 that said that women still accounted for just 19% of players — which is nonetheless an increase of two to four times in 20 years. In a survey of other sources from 2004-2011, RPG scientist Christopher Brace found numbers as low as 16% and as high as 34%.

However, since 1999 the opportunities for female designers have increased, thanks in large part to the two major trends of the ’00s: d20 and indie games.

D20 didn’t change the playing field, but it did widen it. Atlas Games was one of the first publishers to take advantage of this, with Michelle Nephew coming onboard as the company’s d20 line editor. Similarly, Green Ronin — which had been recently founded by Chris Pramas and industry vet Nicole Lindroos — earned its early success through d20 releases. Finally, Paizo Publishing was co-founded and led by Lisa Stevens, who has been frequently mentioned throughout this history; since the release of Pathfinder (2009), Paizo has become the second biggest company in the industry.

Individual women writers also found d20 success. Some past female designers returned with d20 books, while authors like Michelle Lyons, who were just getting their start, expanded their portfolios with d20 releases. Other female authors such as Erica Balsley, Julie Ann Dawson, and Christina Stiles joined the industry thanks to the new opportunities offered by Wizards’ d20 system.

The absence of women is not an accident of fate, nor is it something that will likely change rapidly.

Gary Alan Fine, Shared Fantasy: Role-Playing Games as Social Worlds (1983)

Even Wizards of the Coast increased its female design staff, with new authors including Gwendolyn Kestrel and Jennifer Clarke Wilkes. Shelly Mazzanoble became a voice for some female players through her book, Confessions of a Part-Time Sorceress (2007).

Indie games offered a more revolutionary change to the roleplaying industry. They introduced different sorts of games and different sorts of play. By appealing to a different demographic than the wargame-influenced RPGs of the ’70s, they also attracted a new generation of female designers.

Jenna Moran (previously Rebecca Sean Borgstrom) actually predated the indie movement with her very indie game, Nobilis (1999); she’s continued with Weapons of the Gods (2005) and Chuubo’s Marvelous Wish-Granting Engine (2014).

Other female designers experimented with indie ideas in many ways in the movement’s earliest days. Emily Dresner-Thornber’s indie thoughts mainly appeared in articles, such as those in Daedalus magazine (2003-2004), while CMU Assistant Professor Jessica Hammer was a regular contributor to Game Chef (2002-Present), and Cynthia Miller was a developer for the Cartoon Action Hour (2003) line.

Then, as the indie revolution fully dawned, Ron Edwards encouraged developers to create their own publishing imprints. That’s exactly what many women did in the ’00s, creating the biggest boom of female-led RPG companies ever.

Meguey Baker founded Night Sky Games to publish A Thousand and One Nights (2006) and has since produced Psi*Run (2012) and Valiant Girls (2013).

Emily Care Boss created Black and Green Games, which may be the most prolific female-led indie publisher. She’s released a half-dozen games, the best-known of which are part of her “romance trilogy”: Breaking the Ice (2005), Shooting the Moon (2006), and Under My Skin (2008). She also edited RPG = Role Playing Girl magazine (2009-2010).

Julia Bond Ellingboe founded Stone Baby Games to publish Steal Away Jordan (2007) and Tales from the Fisherman’s Wife (2012).

Anna Kreider created Tasty Bacon Games, which she later renamed to the less in-jokey Peachy Pants Press. She’s best known for Thou Art But a Warrior (2008, 2013) — originally an expansion for Ben Lehman’s Polaris (2006), but now its own game.

Annie Rush originally published her three RPGs through the Wicked Dead Brewing Company, but she has since reprinted Run Robot Red! (2004) and others under her own brand, Itesser Ink.

Jen Seiden, formerly of West End Games, moved on to create her own small publishing house, FireWater Productions, to publish Chaos University (2005).

Elizabeth Shoemaker joined with Shreyas Sampat to found Two Scooters Press. Unlike similar co-founded publishers of the ’70s and ’80s, these two designers have each pursued their own interests through the Two Scooters imprint. Shoemaker’s best-known games are the espionage Blowback (2010) and the romantic It’s Complicated (2008). Deadbolt (2012) was a nominee for IndieCade 2013.

Many other women have created indie RPGs, more than this limited history can cover.

We have different experiences and perspectives that can drive games to new levels of story-telling and world construction, and I believe these abilities provide a much fuller experience beyond number-crunching.

Jen Seiden, “Designing Women,” RPGirl #1 (2009)

Despite — or perhaps because of — the growing numbers of women involved as players and creators, the roleplaying industry is currently beset by a number of gender-related problems. This became particularly obvious when James Desborough wrote his controversial article “In Defence of Rape” (2012), which talked about rape as a plot element, and when a Kickstarter for the feminist “Heartbreak & Heroines” RPG was met with massive misogyny (before it collapsed for other reasons).

Unfortunately, this is part of a trend in the larger hobbyist field that may get worse before it gets better. The comic field has seen animosity directed toward female fans and cosplayers for years. More recently, the issue of female hobbyists exploded rather dramatically in the video game community in 2014 as part of the horrific “GamerGate” scandal — which involved reactionary male players stalking female video game designers, driving them from their homes, and even threatening terrorist actions to stop them from speaking out.

Though it would be easy to be discouraged by this backlash, it’s probably a sign of revolutionary growth — a sign that women have become a significant part of the hobbyist community. That sort of growth is often met by reactionary hate, but things will improve as the industry continues the slow change that began when the first woman picked up a copy of Dungeons & Dragons.

What to Read Next

- For more about the LA gaming scene, including more on APA-L, read The Aurania Gang [PA].

- For more on Jennell Jaquays and The Dungeoneer, read Judges Guild [’70s].

- For some of the earliest RPGs designed by women, read FGU [’70s], Flying Buffalo [’70s], Pacesetter [’80s], and (again) The Aurania Gang [PA].

- For how Jean Wells, Rose Estes, Jean Black, Margaret Weis, Mary Kirchoff, and others fit into a larger narrative, read TSR [’70s].

- For Sue Grau and Hero Games, read Hero Auxiliary Corps [PA].

- For a company that brought many female players and designers into the industry, read White Wolf [’90s].

- For Ann Dupuis’ ground-breaking company, read Grey Ghost Press [’90s].

- For the indie games that grew out of FUDGE, read Evil Hat [’00s].

- For modern companies co-founded by women, read Margaret Weis Productions [’90s], Green Ronin Publishing [’00s], Lumpley Games [’00s], and Paizo Publishing [’00s].

- For more on the indie revolution, read many histories of the ’00s, beginning with Adept Press [’00s]. And for Annie Rush’s part in it, read John Wick Presents [’00s].

Bibliography

Published Sources

Uncredited. 1987. “TSR Profiles: Barbara Young.” Dragon #121.

Uncredited. 1986. “TSR Profiles: Jean Black.” Dragon #108.

Boss, Emily Care, editor. 2009-2010. RPGirl magazine.

Brace, Christopher. 2012. “Women in Gaming.” The Science of Roleplaying. RPGnet. rpg.net/columns/thescienceofroleplaying/thescienceofroleplaying6.phtml.

Fine, Gary Alan. 1983. Shared Fantasy: Role-playing Games as Social Worlds.

Kenson, Stephen. 1999. “ProFiles: Mary Kirchoff.” Dragon #266.

Kim, John H. Undated. “Notable Women RPG Authors.” Darkshire. darkshire.net/jhkim/rpg/theory/gender/womenauthors.html.

Maliszewski, James. Interviewer. 2010. “Interview: Jean Wells (Part I).” Grognardia. grognardia.blogspot.com/2010/02/interview-jean-wells-part-i.html.

Maliszewski, James. Interviewer. 2010. “Interview: Jean Wells (Part II).” Grognardia. grognardia.blogspot.com/2010/02/interview-jean-wells-part-ii.html.

Maliszewski, James, and Allan Grohe. 2009. “An Interview with Lee Gold.” Grognardia. grognardia.blogspot.com/2009/04/interview-with-lee-gold.html. Reprinted in Fight On! #6.

Peterson, Jon. 2014. “The First Female Gamers.” Medium. medium.com/@increment/the-first-female-gamers-c784fbe3ff37.

Ümlaut, Ignatius, editor. 2009. Fight On! #6. Magazine.

Vincent, DM. 2010. “Interview with Jean Wells.” Save or Die Podcast.

Fact Checkers

Emily Care Boss, Janelle Cooper, Ann Dupuis, Jeff Grubb, Jennell Jaquays, Jacq Jones, Michelle Nephew, Jean Rabe, Jen Seiden, Barbara Young

There’s more on this topic, focusing on board games, next month. If you’d prefer a nice PDF, MOBI, or ePub of this and other historical appendi, the complete Platinum Appendix is available from DTRPG.

This is such a great article!