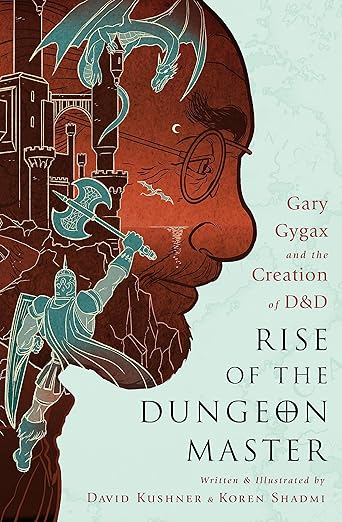

It’s apparently the era for historical looks at the origins of D&D, because this spring saw yet another release, a graphic novel biography of Gary Gygax (and more broadly the game). It’s called Rise of the Dungeon Master: Gary Gygax and the Creation of D&D (2017), written by journalist David Kushner and illustrated by artist Koren Shadmi.

The Contents of the Book

Rise of the Dungeon Master is divided into nine unnamed chapters. They broadly cover:

- An introduction to what Dungeons & Dragons is

- Gary Gygax’s early life, from his youth to the publication of Chainmail

- Dave Arneson and Blackmoor

- The creation of Dungeons & Dragons

- Early computer games based on Dungeons & Dragons

- Dark times: Dallas Egbert III, BADD, and Dark Dungeons

- Hollywood & Lorraine Williams

- The impact of Dungeons & Dragons on the computer industry

- Dungeons & Dragons after Arneson & Gygax

The Art & The Writing

The cartoon art of Rise of the Dungeon Master is beautiful, and well worth the admission price. It’s all attractive gray-scale drawings, but what’s impressive is that it’s clearly been very well-referenced. Shadmi gets the obvious things right, like the covers to various D&D rulebooks, but he goes far beyond that. There are excellent drawings of Arneson And Gygax at a variety of ages. There are pictures of a variety of D&D monsters that mostly look right. Even the illustration of Conan looks like it comes right off a book cover.

The scripting of the comic follows a style that might at first seem peculiar. It’s all in second person (“You”). The intent was clearly to evoke the lives of the creators of D&D (and the D&D game itself) as an adventure. Michael Witwer tried a similar idea in the recent Empire of Imagination, when he dramatized many scenes from Gygax’s life, but Kushner’s adventure writing here works so much better.

Unfortunately the book begins to fail when you get past the very attractive artwork and the well-polished writing …

What We Learn About History

The name suggests that this book is another biography of Gary Gygax, and it definitely isn’t. In fact, it’s really quite scattered. Broadly it’s about the creation of Dungeons & Dragons and its cultural influence on everyone from Stephen Colbert to Van Diesel, but with such a wide focus it doesn’t manage to concentrate on anything.

However, I was much more concerned by the fact that Rise of the Dungeon Master rather casually implies a number of incorrect things about D&D’s history. I won’t quite say they’re mistakes. It’s possible that Kushner was purposefully using the panels of the comic and the dividers between the chapters to elide and sometimes invert events in D&D’s history. That he didn’t mean for chronology within the comic to match chronology in the real world. But the end result is that he creates misconceptions for new readers. (Heck, I had to look one of them up to make sure it wasn’t true.)

Here’s the ones that jumped out at me as I read. Some of them are obviously the result of the sloppy chronology of Kushner’s original writings about Gygax and Arneson being even more sloppily copied into a comic book. But I also suspect some of them arise from a limited understanding of the industry.

Little Wars Was Gygax’s Introduction to Miniatures (25-27). False. In his introduction to the the Skirmisher Publishing edition of H.G. Wells’ Little Wars (2004), Gygax says “I had no idea of the existence of Little Wars or the military miniatures gaming hobby back in the early 1950s, when my friend Don Kaye and I thought we could devise rules for playing with toy soldiers”. He later says, “What a revelation it was when another friend loaned me his copy of Little Wars in the late 1960s. By that time, I was a board wargame devotee and I had played a few tabletop games with military miniatures.” He did play “several battles” using Little Wars with Jeff Perren and says it influenced Chainmail (1973).

Gygax Found His Polyhedrons in the Late ’60s. They included a d10 and a d20 that was numbered 1-20 (32). Largely False. The placement of this event prior to the Summer of ’68 seems unlikely to me. I haven’t hit upon the precise date of Gygax’s discovery of that Creative Publications of California catalog, but the general consensus seems to be that it was somewhere in the Blackmoor-D&D chain of development, which is to say the ’70s. The pictoral representation of a d10 and a correctly marked d20 are definitely anachronisms, and one of the few incorrect art cues that I’ve noticed in the book. The d20 numbered 1-20 apparently appeared in the late ’70s and the d10 more definitely appeared in 1980, possible at Gen Con XIII (1980).

Gen Con Began at the Horticultural Hall in 1968 (33). Incomplete. Yes, that was technically the first Gen Con, but there’s piles of context missing here about the IFW’s early attempts at conventions and Gygax’s own “Gen Con 0” held in 1967.

The Original D&D Classes Were Clerics, Warriors, and Wizards (57). Somewhat False. This uses terminology that was most popular in the ’90s. The original D&D classes were clerics, fighting men, and magic-users.

The Rogue Was Also an Original D&D Class (57). False. The thief didn’t appear until Great Plains Game Players Newsletter #9 (June 1974) and more notably Supplement I: Greyhawk (1975). There’s some more complete information on the topic in Designers & Dragons: The Platinum Appendix.

The AD&D Monster Manual Followed the Players Handbook (72). False. The order is reversed: Monster Manual (1977) appeared first and was largely used as a supplement for existing OD&D games, then it was followed by the AD&D Players Handbook (1978). Omitting the actual rulebook for AD&D, the Dungeon Masters Guide (1979) is also misleading.

The Village of Hommlet Was a Notable Early Module (73). Misleading. T1: “The Village of Hommlet” (1979) was a pretty exciting early adventure for its look at a D&D town, but don’t think it was the first module or anything. It was in fact the ninth. It’s a bit mysterious why the author and artist decided to highlight it here.

Dave Arneson Sued TSR and Fell Out With Gygax Around 1984 (109-110). Way Out of Sequence. Arneson initially sued TSR on July 25, 1979, though there was a second suit on March 27, 1985. But by the time Gygax was about to lose TSR, Arneson had already been absent from it for years.

Steve Jackson Games, White Wolf Games, and Hero Games Follow in TSR’s Wake (117). Misleading. Yes, these companies technically did follow TSR into the RPG industry, but it’s such a random assortment of game companies that it’s somewhat meaningless. They’re all surely notable companies, especially White Wolf, but if you were really talking about game companies that sprang up in TSR’s wake you’d mention more immediate successors like Games Workshop, GDW, and Judges Guild.

Other RPGs Ate TSR’s Market Share, and So the Company Went Out of Business (118). Misleading and Wrong. Technically, other RPG companies must have taken some of TSR’s market share, since shares are by definition percentages. But the whole market was growing so much through the ’70s and the ’80s that that’s not true in any meaningful way. TSR’s sales were increasing year by year. The other roleplaying companies never were really TSR’s competition: they were all second tier, with the first tier ruled by D&D alone. There have only been two times when D&D was not the top dog in roleplaying: in 1997, when TSR was going out of business (for totally different reasons) and in 2012-2014, when Wizards took new D&D products off the market while they revamped the game.

(To be clear: the book gets lots right too; most of the book is in fact accurate.)

The Sources

Kushner conducted an interview with Gary Gygax bout a decade ago: The Life and Legacy of Gary Gygax. This book is largely based on it. In fact a lot of the text is lifted straight from the interview. That interview played loose with chronology, but it was less obvious in the original format; it became a lot more problematic in this second reproduction, one step further from the original truth.

Kushner says that he also conducted additional interviews with Gygax and Arneson late in their lives, but unfortunately they’ve never been published.

The problem with all of this, apart from the sloppiness implicit in the plotting of the book, is that interviews so far after the fact are a questionable source for a book. They’re certainly a valid option, especially when they’re the only discussion of a specific subject. I used plenty of them in Designers & Dragons, but only as a final check or a final option, because they’re one of the least reliable sorts of primary sources. Personally, when I was working on Designers & Dragons, I gave the top level of trust to reports of fact at the time, the second level of trust to interviews at the time, and the third level of trust to interviews after the fact.

(There’s also little new in Rise of the Dungeon Master, other than perhaps some details of Gygax’s youth, which are very nicely gathered together in the first chapter.)

Final Notes

I’ve been talking about books here lately in large part to illuminate new view points on roleplaying history that might be of interest to all of us. I’d hoped that would be the case in Rise of the Dungeon Master too, which was why I bought it and took casual notes as I read.

After I was done I wasn’t sure if I should write about it at all, because I didn’t really want to offer what’s essentially a bad review of a book that could be seen as competition. (Frankly, I don’t think the RPG history category is big enough for there to be competition, so catch them all, even the problematic ones.) But I eventually decided that it was worth writing about to at least discuss the implied misconceptions of the book, and maybe set them right. So, take a look at the beautiful art and evocative writing of Rise of the Dungeon Master, but also be aware of the factual issues I mention here (and feel free to mention more that you discover in the comments … or for that matter mention interesting things you didn’t know!).

This article was originally published as Advanced Designers & Dragons #13 on RPGnet. It followed the publication of the four-volume Designers & Dragons (2014) from Evil Hat, and was meant to complement those books.